-

In the Eye of Precarity

An Essay by Keisha JacobsDe Knoops’ approach is intimate and relational, as he first seeks to build trust and friendship with members of the community, many of whom have experienced financial, emotional and spiritual hardship, which serves as reminder of a quote by American writer and civil rights activist, James Baldwin that reads “anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor."There are many Coloured and Cape Malay visual artists dabbling in various art forms such as painting, sculpture, installation, performance, photography, and videography to shed light on the complexity of Coloured identity, culture, lived experience and sense of community, notably, Imraan Christian, Lady Skollie, Berni Searle, Thania Peterson, Shuanez Benting and Whaleed Ahjum, Igshaan Adams, Tracey Rose, and Hasan and Hussein Essop.The definition of the term ‘gang’ coincides with gang violence, which is commonly systematic and socially meaningful as opposed to being sporadic and instrumental. These parameters distinguish gangs from other youth and delinquent groups that may engage in deviant behaviour. Alongside this, was also the realisation that the American definition of “gang” and its paradigm of gang violence is not only narrow but has been surpassed by post-modern approaches and fundamental shifts in the dynamics of social, economic and political cleavages that characterise urbanity. Cities have become increasingly globalised and as such, Professor of criminal justice, John Hagedorn contends that in order to capture the essence of gangs, one requires an amorphous reflection, in which gangs are simultaneously considered as institutional actors and alienated groups whose secondary socialisation does not derive from conventional educational institutions, but rather from the streets and prisons. In A World of Gangs: Armed Young Men and Gangsta Culture (2008), John Hagedorn explains that the theory posed by the Chicago School holds that it is not only the neighbourhoods, but prisons that play a central role in the origins and growth of gangs and the continuity of gang activity, with French sociologist, Loïc Wacquant arguing that “the spaces of the prison and the ghetto coincide.”In order to locate and understand the factors that lead to the emergence and survival of gangs, one requires a comprehension of the structural conditions in which they exist, while noting that these factors are dually causal and contextual. There is a common association between gangs and poverty, notably, compounding racial marginalisation and existing socioeconomic inequalities, wrought by for example, the absence of employment opportunities and upward social mobility, which has rendered many youth excluded and is found to be the centre of urban violence and crime. This exclusion from the mainstream economy prompts many individuals, but the youth in particular, to resort to organised crime and the informal economy for the purpose of livelihood and to gangs for a sense of resistant identity and guaranteed safety for themselves and their families. Hence, in their text Gangs in Global Perspective (2014), Ailsa Winston states that “gangs may be seen as a barometer of increasingly widespread societal failings.” In addition, urban crime and violence are often characterised by social structures subjected to segregation, spatial polarisation and forced removals of certain populations - as was the case during apartheid South Africa and its impact on Black and Brown communities remains prevalent during the post-apartheid democratic environment. Given these systemic dynamics, another major aspect that research has found to account for the emergence of gang culture is drug trading. The drug economy cannot exist without national and international transit points, which are, as a result of the Group Areas Act of the 1950s, facilitated by many defensible spaces in the Cape Flats that are rarely subjected to police control, as they have the advantage of location with geographic features such as mountains and surrounding affluent white neighbourhoods.

In their text Intimate Connections: Gangs and the Political Economy of Urbanization in South Africa (2010), Steffen Jensen argues that “the security and development nexus takes on specific forms depending on the context, and that in Cape Town's coloured townships it is embodied in policies and practices around what has come to be known as 'the war on gangs.’” Jensen further asserts that it appears that the wars enacted on the gangs in Cape Town are responses to governmental failures and thereby resembles counterinsurgency. This has resulted in a reconfiguration of township citizenship to a state of a “differentiated citizenship”, a term coined by political anthropologist, James Holsten (2007). Situating the term within a South African context, Jensen explains that by definition, the term represents an opposition to the universal rights and inclusivity that was promised for the era of post-apartheid South Africa.Cape coloureds and the broader Coloured community have been widely perceived as the cultural embodiment of gang activity, and this perception is generated and perpetuated by the media and through films such as ‘Four Corners’ (2013), ‘Noem my Skollie’ (2016), ‘The Devil’s Lair’ (2013) and ‘Incarcerated Knowledge.’ Hence, the well-known stereotype of Coloured men depicted and being referred to as ‘skollie’, which is an immensely derogatory and disparaging abstraction.The most notorious street gangs and organised crime groups in Cape Town, are the ‘Hard Livings’, a gang established in the 1960s by twin brothers Rashied and Rashaad Staggie, and ‘The Americans.’These are the two largest street gangs to which smaller gangs, such as the ‘Mongrels’, ‘Dixie Boys’, ‘Ghetto Kids’, ‘The Nice Time Kids’ and the ‘Laughing Boys’, amongst many other gangs, show allegiance and loyalty to.Then there are the numbers gangs or the prison gangs which include the 26s, the 27s, and the 28s. The prison gangs have a feared and prominent reputation in Cape Town, whereby gang wars transcend the milieu of the prison, and are additionally scattered across the Coloured communities of the Cape Flats such as Mitchells Plain, Manenberg, Hanover Park, Lavender Hill, and Elsies Rivier.Gang wars usually centre around territory, women, drinking establishments, drug trafficking and control of transportation routes. Gang violence in these areas are exceptionally rife, often claiming the lives of many members of the communities in which these gangs reside, in worst cases even the lives of children.Cape Tonian artist James de Knoop has embarked on a deeply personal and restorative project which involves photographing and painting portraits of former gang members. De Knoops’ approach is intimate and relational, as he first seeks to build trust and friendship with members of the community, many of whom have experienced financial, emotional and spiritual hardship, which serves as reminder of a quote by American writer and civil rights activist, James Baldwin that reads “anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.”After establishing trust with his chosen male muse, does De Knoop ask permission to create a portrait, with each subject drawn with care and graceful intention. When the portrait is complete, he gifts it back to the sitter, retaining only a photograph of the artwork, hereby avoiding the objectification and voyeurism that always accompanies portraiture of the marginalised.“A big part of my development as an easel painter has been my relationship to a post graduate private easel painting studio in Spencer street Salt River Cape Town, which practically and philosophically skilled me up. In my studies there I developed techniques in portraiture. In searching for faces to paint I entered into the Barbershop and Salon world in downtown Woodstock and Salt River where portraits abound and style is important. Here I found a market and a social debate. This area of an African harbour town is an historic multicultural environment. A lot of history is contained in the many faces. Among others I painted portraits of the board members of the Eastern Congolese community in Cape Town, Friends of Bukavu, Amis Bk. Here I started to learn how powerful portraits can be, the emotions that surround a recognisable painting of someone’s face and my role as a painter. I learned to take great care around people’s identities. I paint images of people - members of communities. A face is a landscape of experience and emotion and for me that is a fascinating exploration in painting no matter who the personality is and each one is so remarkably different. Because the painting recognisably resembles the personality, it is a sensitive and intimate relationship for the person who is the subject of the painting, and thereby the decisions of what is to be done with the painting, in my practice, is the decision of the person who has been portrayed, they are in controlof this avatar in the public domain. As the painter I do not want the responsibility of this exposure of their identity. The personality is my client and as a painter I am in service to them” - James de Knoop.Despite its awareness of racial segretation, systemic inequalities and structural violence, the provincial Western Cape government directs greater priority and emphasis at preserving the image of Cape Town as a cosmopolitan city of digital nomads, and political and economic elites, yet the local population is excluded. This has led to concerns about neo-settler colonialism and increasing gentrification, both of which are influential forces responsible for exacerbating the already high cost of living in the city. Hence, in their text Cape Town After Apartheid: Crime and Governance in the Divided City (2011), Tony Rashan Samara laments that marginalised communities of colour “remain largely invisible from the point of view of urban governance except as potential threats to personal safety and economic growth outside of the townships.” However, the Cape Flats and the more affluent areas in the city centre are situated in a singular geographic location of complexity, as one cannot recognise affluence and privilege without recognising a striking juxtaposition of impoverishment wrought by a racially oppressive past. -

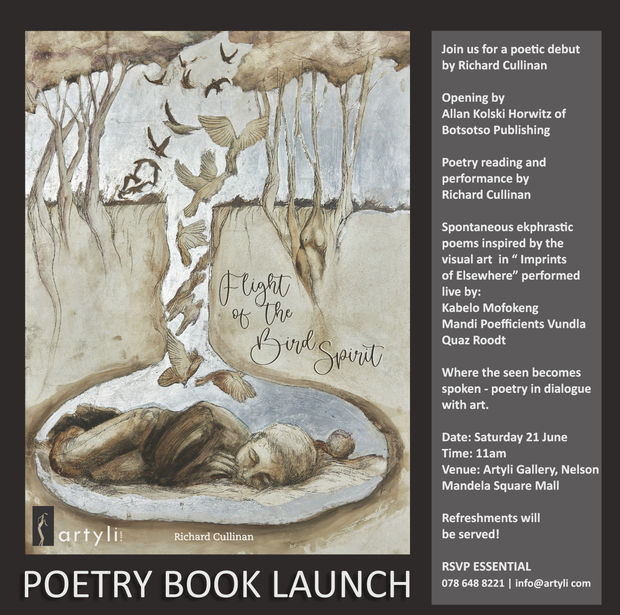

'Flight of the Bird Spirit' by Richard Cullinan

“A quiet triumph of memory and meaning, this poetic debut traces the fragile flight of the human spirit with emotional resonance and haunting beauty.”

-

Digital Spaces; African Art

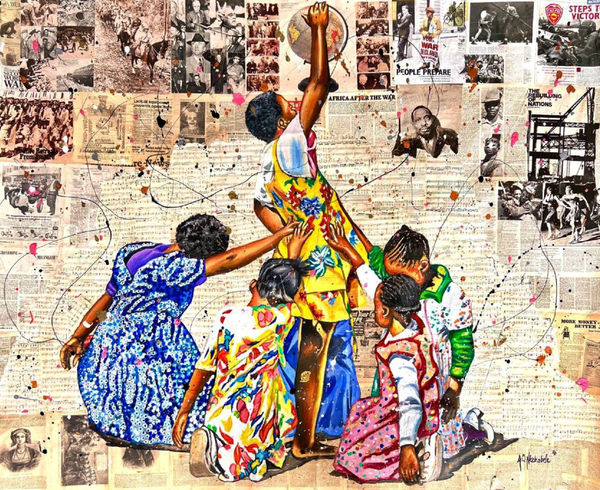

Artyli Gallery Features in 'Black-Owned Galleries Now' Digital Exhibition by Artsy March of the Dimes by Andrew Ntshabele

March of the Dimes by Andrew Ntshabele -

AN ESSAY BY ASHRAF JAMAL AND KEISHA JACOBS

The current digital exhibition is titled ‘Holding Isihawu’, with “isihawu” being the Zulu word for compassion. The exhibition presents questions concerning what it means to be decent during poignantly indecent times and how this can be relayed through the arts.

February is annually observed and celebrated in the United States as ‘Black History Month’, which is a month that commemorates the events and intellectual contributions that have shaped the history of American Americans, and more broadly the African diaspora. The month is a retrospective of Black heritage and Black culture dating back to the Transatlantic slave trade in the early 17th century, to the era of Jim Crow that enforced racial segregation, to the more contemporary #BlackLivesMatter Movement, and to the artists and activists that have cultivated critical Black Consciousness, which originally emerged as both a concept and movement dualy influenced by American minister Dr Martin Luther King, South African activist Steve Biko and African American sociologist and Pan-African civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois.

Artsy, is an American digital art platform and brokerage based in New York City. Digital art spaces grew in significant prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic – as the arts kept the world in contact during an unprecedented period of prolonged isolation and sickness. The artworld has since continued to undergo transformation with the increase of digital art platforms, that challenge the traditional and conventional art gallery, giving rise to evolved forms of creative expression and more global engagement. Artsy is currently spotlighting Black-owned art galleries for Black History Month and Artyli Gallery, as a 40% black-owned art gallery was selected by Artsy for being a contemporary African art space spotlighting Black African artists.This current digital exhibition featured on Artsy includes artworks by South African artists Bambo Sibiya, Andrew Ntshabele, Frans Thoka, Asanda Kupa and Fumani Maluleke. It is through this exhibition, that Artsy and Artyli have collaborated to do what renowned South African art critic and cultural theorist Ashraf Jamal describes as the role of Africa today…’to give the world a human face’.Bambo Sibiya creates declamatory and alluring works that reveals more than what the immediate gaze garners. Sibiya has explored multiple thematic concerns, however his most seminal works are his depictions of the gendered diversity of the Black African experience, most notably, his centralisation of Black women, as the epitome of beauty, fashion, culture and as the holders of the home and the community. Sibiya, does not necessarily reinforce the trope of the strong Black women, but certainly gifts us with artworks that embody the protective and revolutionary spirit of the South African chant, “wathint abafazi, wathint imbokodo” which translates to “you strike the women, you strike the rock.” While Sibiya’s works are commemorative and empowering, they are never illustrative, rather, the persuasiveness of Jacques-Louis David’s paintings come to mind – a carrying of rhetorical force.Andrew Ntshabele is known for his motif – soulful depictions of mothers and children, painted over collaged backgrounds seeped in African history. While history hurts, as the American cultural analyst, Fredric Jameson reminds us, its pain can also be overcome. In Ntshabele’s artworks the joy of children are the blessing and the inspiration. Here the Black children are seen. Buoyancy is the striking energy, the subtle interplay of sepia and rich colour, earthiness and splendour. Given the sentimentality that typically informs how children are seen, Ntshabele asks us to weigh innocence and growth, to maintain purity despite ruin. Given that in many of the paintings the women and children are seen from behind – as though removed and separate – suggests that the painter wants us to be privy to worlds beyond our ken. Intimacy yet distance is the means through which the paintings ensure their enduring pleasure.Frans Thoka implicitly addresses the disenfranchisement and enslavement of South Africa’s Black majority under colonialism and apartheid. For Thoka, the role of art is to serve as a reminder of this historical betrayal, but also, to do so through understatement. The monochrome colour scheme used in the artworks of Frans Thoka, shifts between grey, black and white, and most recently hues of brown have been incorporated, is commonly used in South African resistance art. Frans Thoka uses variations of blankets – notably the prison, the migrant and the Basotho blanket as an inspirational material, to drive his artistic message which sheds light on conversations surrounding culture and history, that have shaped Black pain and oppressive systems. Thoka’s main theme is rooted in the memories of the land, such as those forcibly removed, alongside those who have been silently buried within it, remaining ungrieved. What we then encounter are Thoka’s creations of mixed media landscapes that tell an implied story of dispossession, viscerally connected to suppressed pain, yet ultimately exalted.Fumani Maluleke depicts the duality of African life. At first, Maluleke literally expresses African heritage and rural living through the medium of grass mats on which undisturbed natural scenes of green and brown hues of Earth and blue skies are painted. There is a literal element of specific spatiality featured in the artworks of Maluleke that are linked to childhood memory and an upbringing not overcome by the rapidity of urbanisation. Maluleke’s artworks have a still impact that encourages thoughts of communal living with a slower pace and greater connection to the environment. Maluleke additionally dabbles in figurative paintings that capture traditional ceremony and ritual rooted in African townships and their moments of vibrancy and celebration.Asanda Kupa’s impasto-laden paintings merge abstraction and figuration, layering earth-toned textures with human forms. His interplay of light and dark elevates social narratives of marginalization, creating deeply introspective works that balance historical context with raw self-expression.In closing, upon reflection, it appears that collectively, the artworks of Bambo Sibiya, Andrew Ntshabele, Frans Thoka, Asanda Kupa and Fumani Maluleke, offer dual reflections of Black African life and how African contemporary art advocates for greater humanity amidst uncertain times, because if understanding matters, it can only be achieved through love, through compassion. -

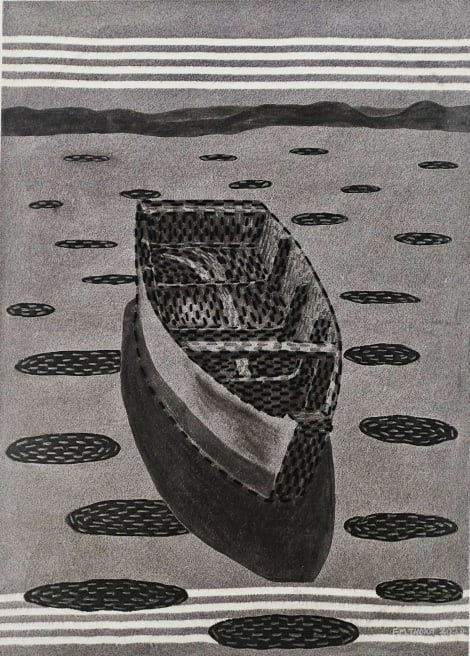

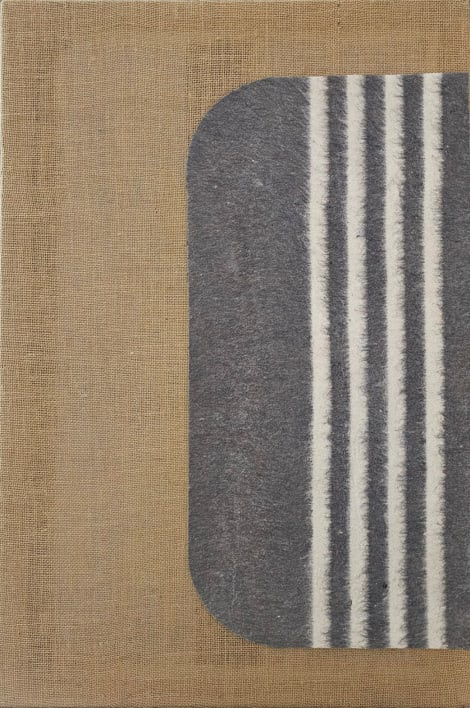

Frans Thoka: Land as the Silent Witness in Monochrome

At Artyli Gallery, Frans Thoka’s Latest Exhibition Reflects on South Africa’s Complex History as Explored by Ashraf Jamal. Published in Art Africa, 10 October 2024 -

Frans Thoka’s gallerist, Karen Cullinan, and I, are driving through Johannesburg’s downtown warehouse district in what looks and feels like a hummer, an all-terrain military vehicle. The sky is a greyscale – slurries of thin and thick black ink – a storm is about to break. Between a grey sky and broken asphalt beneath, we enter Thoka’s studio which, too, is tonally grey.

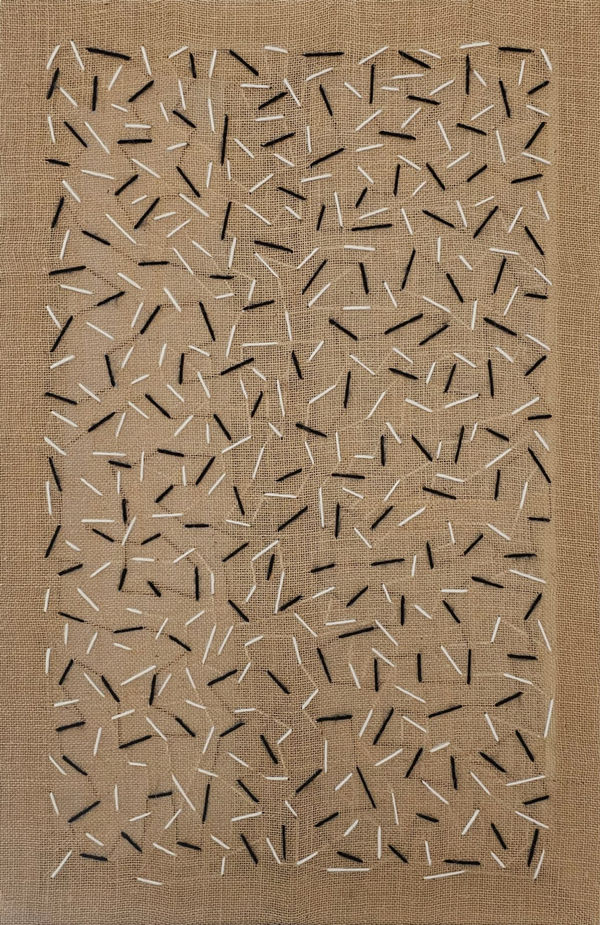

A grey skip crammed with off-cuts of 100’s of meters of grey blanket material sourced from Aranda occupies the center. A bolt leans against the wall which is lined with artworks at various stages of completion. The overall impact is emphatically monochromatic, though quiet moments of colour – deep blue, earthy green, hessian the colour of wheat – make their entrance. Grey, however, is the defining colour, or rather black, its monochromatic source.The defining colour, or non-colour, in South African resistance art, monochrome, black on white, signals the didactic and graphic, an expression that is narrow or narrowing, preoccupied with a precise interrelation of form and content – ‘statement art’. This, however, is too simplistic a view, for resistance art – art against an oppressively racist and unequal apartheid system – was never that reductive. Urgent and pragmatic, true, but the illumination of black consciousness never supposed a rallying ideology alone. In I write what I like, Steve Bantu Biko sums up the complexity of the struggle: ‘The first step … is to make the black man come to himself, to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity, to remind him of his complicity in the crime of allowing himself to be misused and therefore letting evil reign supreme in the country of his birth. This is what we mean by an in-ward looking process. This is the definition of “Black Consciousness”’.Murdered on September 12, 1977, Biko’s legacy lives on in the art of Frans Thoka. Its function – if art can ever be reduced to its aim or intention – is to work through grief, acknowledge on-going suffering, and, in-and-through the making of art, perform an exorcism. If the ‘miner’ or ‘prison’ blanket is Thoka’s defining trope, it is because it carries the burden of Black pain, and its revelation. But it is not only the symbolic power of the miner’s blanket that matters but also its uneasy consolation – the white-striped grey blanket conceals the sleeper as the land conceals historical pain.As the South African Nobel laureate, J.M. Coetzee, reminds us in Age of Iron, the Black dead continue to groan their woes beneath ‘the skin of the earth’. There remains the urgent need for a cleansing of that vision, or, after African tradition, of putting medicine into the grave – a way of telling a story through words and paint and dance of a land reborn, so that ‘each time one of us touches the soil … we feel a sense of personal renewal’. These last words are by Nelson Mandela, from his 1994 inaugural speech, one which remains a great promise deferred in what is none other than a phantom democracy.Titled Ba ile Kaae / A Way to Reconcile – Chapter 2, Thoka’s solo show at Artyli in Johannesburg – followed pell-mell by a group show at Scope in Miami – acknowledges the land as a source of pain and hope. His art, however, is not a morbid retention of suffering. Rather, it advances through the embrace of pain, towards reconciliation. In this self-congratulatory hour in which Black portraiture reigns, Thoka reminds us that change is never simple, that Black life, after Biko, remains to be invigorated, transfigured, rendered inspirational.As to how Thoka practices this advocacy? He does so quietly, softly, through tones of grey, layered textures of black oil paint, stitched and glued collage, the effect of which is silhouetted and intrinsically flat. If depth of field is secondary in Thoka’s collaged blanket-works – while primary in his drawings on Fabriano and hand-made paper – it is because the artist’s approach is fundamentally abstract – Thoka elicits emotion. His artworks, like sonar, evoke or sound suppressed despair and yearning. For what Thoka can never forget is the catastrophic consequence of the Natives Land Act of 1913, in which, under British rule, 90% of the land was given to a white minority, a calculatedly devastating legislation that left South Africa’s Black majority landless.In her collection of poems, Mine Mine Mine, Uhuru Portia Phalafala sums up the impact of this brutal and cruel legislation which resulted in ‘Social death, communal death, familial death / ambiguous loss … the loss of fatherhood when you had children / the loss of manhood when you were infantilized and called boy / the absence of your divine humanity in your ancestral land’. In Thoka’s art, this psychic disfigurement runs deep – it is never graphically represented. Rather, by operating elliptically and inferentially, Thoka returns us to an ancestral land that remains benighted. Over a century has passed since the Natives Land Act, and still land redistribution, restitution and reconciliation, remain deferred. Nevertheless, for Thoka ‘land is the observer of truth’, its mute witness.Raised in Northern Limpopo, by his parents in the township of Marapong and his maternal grandmother in the rural village of Ga-Maja, Thoka understood both the tension of a congested disenfranchised community and the solemn solace of wide-open spaces. He speaks with great relish of the illicit pleasure of ‘crossing fences and travelling through bush’, of his passion for Indigenous plant-life – cacti, aloe, acacia – of ancient burials beneath enduring trees and secret pacts – his a childhood that has endured and shaped the nature of his art fundamentally.If Gustave Courbet, in his painting Burial at Ornans (1849), sets a commemorative stage, the rural community of varying social stature arranged about a vacant black hole at the centre, then Frans Thoka, unceremoniously, conjures an erased, unnamed and nameless history – an invisible truth. We discuss a cut-out elongated black shape with a rounded tip. A coffin, I ask. Thoka smiles. An entrance to a cave perhaps, he says, or, the silhouette of a cactus or gravestone.Dressed in charcoal overalls, blue and steel fabric scissors in hand, illumined by a low grey light pouring thickly through a bank of industrial windows, Frans Thoka is the youthful embodiment of an ethical complexity. Unmoved by any triumphal zealotry, firmly focused on human paradox, snagged between tragedy and hope, he has chosen to gift us a dilemma. How do we move forward? How do we reconcile what remains irreconcilable?That said, there has been another human presence in the studio throughout – Frans Thoka’s little son, Lesedi. In between discussions about art, Lesedi and I have been pulling faces. I take a photograph and find him with eyes agog, joyous, hearty … pure. -

Whispers in Matter

An Essay by Ashraf Jamal. Published in Art Times, October 2024 -

We travel blind … intuitively. Through this core orientation, this means of moving through the world, is also the lesson expressed by all the artists. Some may need a more organized system, others not, but all, in their different ways, invite us kindly, gently, into realms ultimately trackless, with no finite spoor. We need some light to carry us along … some inner light, some thrumming soul, some fathomless longing.

The new group show at Artyli Gallery – Whispers in Matter – is a reminder that art is about feeling. All our senses are triggered. Touch meets sight … smell meets sound. The sum of our truth is the sum of our senses. Even the mind, mistakenly considered to be Reason’s chapel, is a sensory and intuitive organ. It is not the ‘Empire of Signs’ that matters but the Emporia of the Senses.

It is unsurprising that the curatorial vision veers towards abstraction, and finds the figurative inside of it. In his manifesto on abstraction, Jerry Saltz discovers an enchanted realm, art as a visionary tool – the best ‘ever invented by human beings to imagine, decipher, and depict the world’. For ‘abstraction not only explores consciousness – it changes it’. This is because abstraction, or art more generally, is not as objectifiable as we would like to think. Rather, art ‘exists in the interstices between the ideal and the real’, between projection and sensation. This is because, above all else, it is a sensuous expression, no matter how chilling, how warm. What one connects with when one listen, tracks, navigates, or inhabits an artwork is ourselves. Art is elemental, it is earth, water, sky. It is we who become a divining rod.Talia Goldsmith’s series ‘Singing Roots’ is a love-song to listening and to making. Inspired by memory, which is none other than instinct, she notes, on completing a sculpture, that it is she who was now embraced ‘in their harmony’. The making of art completes one, it momentarily makes one whole again. It was then that she realized that her grandmother’s song had accompanied her throughout the creative process – ‘Each sculpture in tune with its internal voice. Each sculpture a singing root. Each sculpture bearing witness that I did listen’.Another sculptor, Robert Wagener, too finds solace in the process of making his ceramic forms which, for him, evoke ‘the volcanic origins of the earth itself’. It is the grounded nature of Earth that is the artist’s creative forge. His thickly stratified forms speak of a ‘deep time’ which, for Robert Macfarlane, evokes the rich density of existence. Clay, made of earth and water, is the most primal source of human creation – a reminder that we too are made of the same matter – for the earth’s cycle is ‘dynamic’. ‘Mineral becomes animal becomes rock; rock that will in time – in deep time – eventually supply the calcium carbonate out of which new organisms will build their bodies, thereby re-nourishing the same cycle into being again’. Matter is never inanimate. Never truly silent.If art requires a listening ear and a sonorous heart, it is because it is life. Or, as the sculptor Louis Bourgeois eloquently phrases it – ‘Art, no less than wisdom, waits on life’. Art exists because we are alive. Art exists in and through human life through all eternity. It is this synergy that is the core of Toni-Ann Ballenden’s relief works. Almost geological in the impression they yield, seemingly akin to fossilized remains, they echo Macfarlane’s notion of deep time. The earth is a gestating secret which those, who are able, can reveal to us. Ballenden is such an artist. A conjurer, a seer, she unlocks and unriddles, then plunges us back into an enigma. This is because the world’s wonder can never be wholly revealed. Her art is a mantra, it is talismanic. As such it requires only that we share a mystery. Trace elements abound … gnomic residue.Raja Oshi shares this elemental preoccupation. Like Goldsmith, Wagener, and Ballenden, Oshi is drawn to earthen tonalities, earthen mysteries. Her bodies are shadows on a cave wall, her geometry is ancient. In joining the human and abstract realms – in reminding us that they are indissoluble – Oshi returns us to a humanity that long predates the eighteenth-century Enlightenment ideal, the self-fulfilling fantasy of rationality, power, and control. Instead, we are returned to more durable intimacies, to an ancient order, an ancient love. As the Greek philosopher, Pythagoras, reminds us – ‘Geometry is knowledge of the eternally existent. Number is the within of all things. There is geometry in the humming of the strings. Time is the soul of this world’.Once again, we return to whispers in matter – the geometry of sound … the soul that lies inside of things. ‘Souls are mixed with things; things with souls’, the anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, reminds us in The Gift. This is because of the sacramental nature of life, how we honour our lives and the lives of others through creation. It is not vain for Wagener to conceive of a ‘successful’ sculpture startling the viewer, to wish that his creation ‘draws them in and ultimately never lets go’. For despite the transitory nature of life, and the longed-for eternality of things, the hope for the endurance of the things we call art, through love, is an all-too-human goal.Like Raja Oshi, Daniel Chimurure also conceives of art as an incarnation and a ghosting – as a trace element. Toni-Ann Ballenden also shares this perspective, though hers is more primordial. Chimurure’s ghost-world is more immediately present. A combination of raw collage and paint, the world Chimurure evokes is as abstract as it is suggestively figurative. The works are illumined yet not, despite the peculiar presence of an abnormally large light fitting or globe. Once again, we are returned to Plato’s shadowy figures reflected on a cave wall, though in Chimurure’s case, unlike Oshi’s, there is no sacramental sustaining union. Desolation creeps in … isolation too. We are perhaps caught in the pathos of loss. Is it true, as Kurt Cobain remarked, that ‘all alone is all we are’? Or is Chimurure not also helping us to find companionship in our loneliness, or aloneness? Is love the great and most enduring whisper?Hussein Salim and Lynette van Tonder, by way of comparison, share a passion for colour – though here we should acknowledge colour’s tentative presence in Chimurure’s art. In Van Tonder’s works the delineation, however, is much stronger, the artist inviting us into boldly rendered cartographies in which people and places – being and space – are enmeshed. Density is the key to Van Tonder’s creative expression. Sometimes that density is becalmed, on other occasions it’s a maelstrom. The mood-shifts are vital. For her, questing is the driving force – be it a quest for self or a quest for community. That this occurs inside a ‘grid’ is a reminder that chaos requires order, that error requires grace, and that Van Tonder’s art, no matter how turbulent, requires a ‘course correction’.Are artists the mapmakers of the soul? Are they our guides into higher and nether worlds? Do we long to be taken on unbidden journeys? Is that why art – especially art that is not easily decipherable – our greatest elixir? Why else would it draw us so deeply inward, before expelling us? Why would it sound its siren song, whisper its enchantments? Perhaps because, as ‘the greatest visionary tools ever invented by human beings’ it allows us ‘to imagine, decipher, and depict the world’ – to read it as a scroll, some cypher, some uniquely compelling riddle. Therefore, if this exhibition matters, it is because it allows us to enter the portal of our choice, for in life, if we are not beckoned, we fear that we do not exist.Hussein Salim captures the pathos built into the creation of art. ‘For me, art not only evokes memories and contemplation of the loss of home but it also encounters the present and shapes the future.’ It is the entire creative arc that Salim evoke. If loss is inescapable, so is yearning. Nothing truly dies, all of life is regenerative. This is Robert Macfarlane’s point in his book, Underland, and it is also the vital point expressed by every artist in this exhibition. Salim’s expression thereof is eloquently subtle, even quiet. We enter gentle worlds in which light and shade dance about, in which worlds hover as much as they recede. We are buoyed, held aloft, carried. At no point are we ever lost in a painting by Salim. Unlike Van Tonder, he navigates us through the world without a discernible grid. -

Mothers and Children

An essay by Ashraf Jamal. Published in Art Times, August 2024 -

A deeply spiritual humanist – a painting begins with a prayer – Andrew Ntshabele’s work is devotional.

Mothers and children are iconic themes in the history of painting, the embodiments of grace, purity, and sanctity. One need only consider the staple of Christian faith, the Madonna and child. But like all objects of sentiment, and sentimentality, mothers and children, throughout history, have always also been the victims of abuse. It seems that we cannot separate the light from the dark, adoration from hatred. It is the perversity of this axis that deserves our attention, particularly today, in South Africa, in which abuse is pathological.

There are innumerable reasons for this, most notably colonization and apartheid, two related systems of oppression founded on the enslavement and bondage of black life and, subsequently, the devastation of family, community, custom and tradition. The subsequent alienation proved not only materially destructive, but psychically too. The root of abuse, by men of women and children, is deeply connected to disempowerment and rootlessness. However, to solely assign blame to the destroyed black man is to miss the mark.The Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, in which sixty-nine people were murdered, including eight women and ten children, was designed to quell protest against the passbook or ‘dompas’ – the most despised symbol of apartheid. Abuse, therefore, is complex. But it is its endemic nature, its perverse normativity, that remains concerning thirty years after the inauguration of South Africa’s democracy. The cycle of light and darkness, sentiment and hatred, prevails. It has become monstrously natural.

In the same year, in reaction to the Sharpeville Massacre, Ingrid Jonker penned the poem which Nelson Mandela would read in his inaugural speech. It is a poem about freedom from enslavement: ‘ The child peeps through the windows of houses and into the hearts of mothers the child who just wanted to play in the sun at Nyanga is everywhere the child who became a man treks through all Africa the child who became a giant travels through the whole world Without a pass.If utopian, Jonker’s vision remains just. All those who have been oppressed must be freed, no matter the perversity and damage that would wish it otherwise. It is this principle that runs through the paintings by Andrew Ntshabele. His visions of mothers and children are observed at a distance, at play, in repose, in joy and in rest. As such, the paintings are consolatory – their purpose is to ease the soul. Caught between sepia and bright colour, they are both earthen and ordinarily ceremonial. And it is pointedly, and poignantly, their ordinariness that matters. Ntshabele is unconcerned by the rictus of extremes that holds the country in its thrall, the pornographic spectacle of pain, or the morbid entitlement that comes with the extortion of an historical burden. It is not justice Ntshabele seeks but peace and atonement. This, for the artist, is achieved counter-intuitively, by refusing to fall prey to systemic abuse.Three barefoot children walk away from the viewer, arm in arm. Four young girls, again turned away from the viewer, perform a dance with arms upheld. Young children race from a scene in some excited anticipation. Children sit cross-legged in a circle, rapt in deep mutual attention. Mothers sit in a separate gathering from the faintly outlined men in the near distance. These are not paintings which force a reckoning. Ntshabele’s deliberate refusal to produce an engaging sightline, in which the viewer meets the eyes of the painter’s subject, resists complicity. ‘Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other’s eyes for an instant’, Henry David Thoreau asked. ‘We should live in all the ages of the world in an hour; ay, in all the worlds of the ages’. It is the wonder on mutual insight that compels Thoreau. Not so Ntshabele. If his worlds are seen askance, it is because a deeper wonder in humanity is possible through vicarious observation. Given the historical objectification of the black body – black life – all the more does the artist seek the sanctity of the prosaic and unremarkable. In this regard, Ntshabele concurs with the view of the celebrated cultural thinker, Njabulo Ndebele. ‘The ordinary day-to-day lives of people should be the direct focus of political interest because they constitute the very content of the struggle, for the struggle involves people not as abstractions. If it is a new society we seek to bring about in South Africa then that newness will be based on a direct concern with the way people actually live’. Ndebele’s view underscores Ntshabele’s vision. For both the painter and writer, it is the miraculous nature of the everyday that is the greater boon.Ntshabele’s paintings, however, are not merely documentary records of everyday life. The naturalistic deportment of his mothers and children is certainly the key, but their location and framing signals a parallel conversation. Against a wall, just beyond a gathering of children, we see a dense collage of layered newsprint and images. A dense colonial-historical timeline? A counterview to the innocent grouping at the fore? ‘History hurts’, Frederic Jameson remarked.But what is the nature of Ntshabele’s relationship with history? Is it ever-present? And if so, is there in fact no redemption? Is Black life forever shadowed by its oppressor? Given that the mothers are seated on a mat of shredded newsprint – the words ‘racism’ and ‘flames’ glaringly in our sightline – supposes that the vaunted quiet and calm the figures emit, is also transected by a violent history. Is there no escape? Is innocence an illusion? Or is innocence not all the more vital despite the reality of embedded pain?How one reconciles this tension in Ntshabele’s collaged paintings is critical – it will determine their reception and its outcome. What cannot be ignored is the complexity of the fate of mothers and children. To idealise someone is also to diminish them. The sacred and the profane are inextricable. However, what matters in this fathomless realm of wrong is how and why one prevails – the goodness that remains, the beauty too.Andrew Ntshabele is no sentimentalist. However, like the celebrated poet, Ben Okri, he understands the enduring power of prayer and sacrament. In the poem he penned in honour of Martin Luther King’s famous speech – ‘Children of the Dream’ – Okri writes:They want the earth and the stars

And the beautiful heavens.

They want to be free

And they want the possibilities

That freedom brings. And also

Freedom’s weight and dark side.

They want to love who they want.

They do not want to be defined.

They do not want to be limited.

They do not want to beg for

Their humanity, or the right to be

Creative, or different, or unexpected

Or wild, or surprising, or defying

Of boundaries. They do not want Condescension, or assumptions.

They want to rebel, even against Themselves. They want to celebrate,

Even that which didn’t celebrate them. -

On This Good Earth

An Essay by Ashraf Jamal. Published in Art Times, June 2024 -

In his inaugural address on the 10th of May,1994, Nelson Mandela declared, with ‘no hesitation’, that every citizen ‘is as intimately attached to the soil of this beloved country as are the famous jacaranda of Pretoria and the mimosa trees of the bushveld. Each time one of us touches the soil of this land, we feel a sense of personal renewal… We are moved by a sense of joy and exhilaration when the grass turns green and the flowers bloom.’The natural motif central to Mandela’s speech was by no means accidental, for what the great leader sought to foreground was the inextricability of nature and humankind, place and citizenry, and the seamless interface of the so-called ‘alien’ jacaranda and indigenous mimosa. ‘That spiritual and physical oneness we all share with this common homeland explains the depth of the pain we all carried in our hearts as we saw our country tear itself apart in a terrible conflict and as we saw it spurned, outlawed and isolated by the peoples of the world, precisely because it has become the universal base of the pernicious ideology and practice of racism and racial oppression.’Fast forward thirty years and, today, we find ourselves still striving to overcome a pernicious ideology that informs the instability and turbulence of the current moment. But it cannot be ignored that, finally, we are revisiting Mandela’s great ethos in a bid to build a government of national unity, a reconciled and wholly inclusive citizenry, a new era as wondrous as greening grass and blooming flowers, as joined as the jacaranda and mimosa.It is in this greater unifying spirit that Karen Cullinan, curator and director of Artyli Gallery in Sandton, Johannesburg, presented a group show, titled Soil, in which the earth we all occupy, through which we are natally and historically shaped, proved the decisive connective tissue. For as Mandela optimistically reminded us, when we touch ‘the soil of this land, we feel a sense of personal renewal’.While this generative power is certainly the core spirit of the group show, we cannot ignore the toll of history and burden of pain which informed the art of Frans Thoka in particular, because for him the rind of earth on which we stand also conceals a deeper loss and hardship – the historical fact that in 1913, under the Natives Land Act, 90% of the land was handed to a white minority, and the black majority left landless, displaced, without the ability to truly root themselves.The traumatic consequence of this loss remains trenchant, and, in a conversation with the artist, it could not be suppressed. For if the land is a key motif in his paintings of cacti, irrigated earth, gravesites, scarified patterns that conjure wormholes and terrestrial rupture, what cannot be ignored is the surface on which Frans Thoka’s unsettling pastoral scenes are cut and threaded – namely, Basotho or ‘prison’ blankets in grey with white stripes. An archetypal and generic material, a cipher for warmth and rest, but also for displacement and migrancy, the blanket is a Janus-faced emblem-medium-tool. While the affect of Thoka’s paintings is easeful, the grey palette quietly consoling, the artist nevertheless remains insistent regarding the continued unrest which an artwork, formed from a definitional trope of bondage, conceals or suppresses.If Thoka’s vision is burdened by pain, if, for him, a graveyard is a sacred place to which one returns, through which one protects oneself, for Asanda Kupa, say, it is not a place as despairing. His thickly painted pastoral scenes, in which black community is the central seam, express a ‘subterranean solidarity’, some hidden connectivity that overcomes any internecine conflict or rupture. His community is bonded to the land and inseparably allied with the heavens. If Thoka remains snagged within history, Kupa’s vision is metaphysical. If, after John Fowles, ‘It is far less nature itself that is yet in danger than our attitude to it’, then, for Kupa, what should be changed is our ‘attitude’ – how we relate to the earth, to community, to nationhood, how we construct and reimagine a sense of place. This is certainly seminal to Mandela’s inaugural speech, in which hate must be overcome, despair endured, hope, above all, cherished.This temperament is markedly present in Fumani Maluleke’s paintings made on grass mats. Another staple and symbol for rest, it conjures Maluleke’s record of his birth, precisely on one of these mats, and, more metaphorically, its generative relationship to the earth. After all, grass mats come from the earth, they are woven, collectively made and used, long before their imaginative retooling as supports for painting. However, if the miner’s or prisoner’s blanket carries an ominous history, the grass mat is wholly affirming – as beautiful as Mandela’s vision of greening grass. As for the content of Maluleke’s paintings? They too are largely records of pastoral or bucolic scenes, with benign visions of townships thrown into the mix. This is because Maluleke resists sorrow, because his vision is bonded to a fecund and nurturing earth. As for the overcast skies in his paintings? They are only portentous in so far as they auger rainfall.That Maluleke chooses to tear apart the matting, allowing the dried grass to break away from the two-dimensionality of its planar surface, suggests an artist for whom materiality is as vital as the representational. This formal self-awareness is as evident in Kupa’s raw and rough painterly surfaces as it is evident in Thoka’s indented and stitched blankets. In each artist’s work the surface is distended. In each there is a keen grasp that art is never neutral, always uniquely made. That Africans, in particular, have demonstrated a stratospheric reimaging and retooling of global post-industrial waste – computer innards, say, global surplus of all kinds more generally – proves an acute reminder that no continent is better equipped to survive human excess. In the case of the paintings of Frans Thoka, Asanda Kupa, and Fumani Maluleke, we find a potent grasp of community, survival, and transfiguration.Yet another artist shown at Artyli, and present in the shared conversation, was Henrico Greyling. A sculptor rather than a painter – though he practices in numerous styles and forms – Greyling too is acutely aware of the criticality of the earth as our beginning and end. However, if Maluleke has titled a show ‘No time like the future’, Greyling has titled his seminal installation ‘Archway to yesterday’. Maluleke’s vision is anticipatory, while Greyling’s is nostalgic. This is because he understands the vitality of the past as a site for renewal. His deconstructed steel archway – imaginatively conceived as a way-finder, a portal through which to return to his grandmother – is a reminder, after the great poet, TS Eliot, that ‘Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future, / And time future contained in time past’. In other words, time does no operate causally, it possesses no beginning-middle-end, but is caught always in some ‘eternal present’.If Eliot’s view is timely, it is because it reminds us that all of life, whether good or bad, returns, that evolution is elusive and illusionary. After all, ‘What might have been and what has been / Point to one end, which is always present’. Perhaps this is the lesson we must learn. That Mandela’s inaugural speech delivered thirty years ago remains ever-present. That the momentous historical moment in which we now find ourselves – the creation of a government of national unity on June 14 / the fight for liberation on June 16 – are the signals of promise in the now, in this moment, in which we also find ourselves reflecting on the art of four artists.

-

Bambo Sibiya: Black Becoming

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

Contemporary art and art spaces are increasingly emerging as the locus for critical conversations ranging from liberation to intersectional injustices, all of which have been conjured through beguiling representations of complex realities. Artcan then be considered as an imperative cultural catalyst for social change and a necessity for the human spirit, fostering individual solace and collective contemplation.Social Realism is an art movement that emerged with the onset of World War I and World War II in response to the prevailing social condition present during those periods. Social Realism is notably associated with the era of the Great Depression of the 1930s that occurred in the United States. The movement was particularly critical of the adversity endured by the working class across social, economic and racial contexts. The Social Realism movement expressed its contempt through the visual mediums of painting, sculpture, photography and literature.Sibiya is influenced by and subtly incorporates characteristics of Social Realism, to foreground socio-political issues endured by the marginalised. Sibiya highlights the flaws of society by touching on topical themes such as the politics of social inequality, racial segregation, and migration. Most of Sibiya’s inspiration is derived from the stories of single mothers and migrant workers - their sacrifices and strength.Sibiya's most prominent works have centred on the subculture of Swenkas in Black townships. Swenking originates from an ancestral Zulu tradition of a cappella singing, known as ‘isicathamiya’, which was traditionally practised at celebratory events such as weddings and cultural holidays. Later on, as a culture of respect and style, ‘Swenking’ emerged in the 1970s as a competition between Zulu men living in worker’s hostels, who were working as migrant mine workers in the city.Swenka culture is both a ritual and a form of performative art perceived to have developed in response to rapid migration owed to the advent of the mining industry in South Africa during the era of apartheid.Swenking evolved as a cultural practice of resistance and as a socio-political statement against the prevailing economic order and contexts of poverty and oppression. Swenka culture provided a protected space of freedom and seminal moments of Black joy and Black pride.Swenking is said to be “a conscious enactment of dandyism”, notably Black dandyism, as a self-fashioning historical subculture that has given new meaning and new contexts to existing and established cultural styles. Swenkas embody elegance, affluence and a form of refined masculinity that at times alludes to gender fluidity. Swenkas have used the body as a site on which to express identity through sartorial choice and attitude. Merging the modern and the traditional, the cultures of Europe and Africa, Swenka’s have created a cultural hybrid of urban fashion, and a cosmopolitan identity in the globalised era.In her text, ‘Portrait of a Gentleman - Swenking and the Reactualisation of Dandyism in South Africa’, Daniela Goeller writes that Swenking “helped to create a modern Black identity, reflecting conditions of urban living, an intention for creating social cohesion and maintaining tradition and cultural practices, resulting in a form of appropriation and creolization, fundamental to post-colonial societies.”Sibiya’s depiction of Swenka culture is one in which Black identity becomes wealth, becomes abundance and becomes cosmopolitan. Sibiya conceives of Blackness as a way of being without limitation, that cannot be confined. In so doing, Sibiya deviates from the single story that has historically perpetuated stereotypical associations between Blackness and poverty.Prolific Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie speaks on the dangers of stereotypes stating that “the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”1. Goeller, D. 2016. Portrait of a Gentleman - Swenking and the Reactualisation of Dandyism in South Africa.

-

Asanda Kupa: Subterranean Solidarity

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

The presence of ideology in a work of art often goes unseen or unnoticed by the spectator, yet the prevailing ideology does express itself in the message or the absence of the message - that is what the work says, and equally, what it does not say. To critique the history of class and the practice of exploitation as referenced in art is to analyse art from an economic perspective, hereby creating a relation between culture and the economic fundamentals of a society.Asanda Kupa works in the liminal space that exists between historical context and self-expression, hereby capturing social realities of the marginalised while reaching for the heights of creative expression through an intuitive and introspective art process.A Marxist analysis of art holds that art can only capture the context in which it emerges. The idea that art solely derives from the heart and spirit of the artist is a myth emerging from an aspect of bourgeois idealist philosophy. That is to say that the artist, as a cultural producer, creates art as a cultural product, which is possibly a cardinal component of the human condition, reflecting prevailing conditions in human society. The artistic calling then is essentially to reflect on space and time given that both art and artist are tethered to the culture of a society and its larger socio-political contexts.Kupa visually protests on behalf of the people, particularly blue-collar workers of the working class. Kupa incorporates a subtle Marxist philosophy in his work by highlighting the class conflict that exists between the proletariat and bourgeoisie. Kupa advocates for a return to community while probing into those power dynamics at play that engenders unequal distributions of wealth and resources in capitalist societies.The traditional association between art and mining can be traced back to the 19th century, with mining art particularly focusing on the controversial politics of the mining industry. The mining industry has cultivated artistic interest in emotive themes that respond to the anxieties of death and claustrophobia. Many artists often choose to empathise with mineworkers forced to work in confined conditions underground and with the families of mineworkers who became victims of mining disasters.The works of Asanda Kupa touches on the intersection between mining and migration by spotlighting the plight of mineworkers, both physical and emotional. Kupa illustrates a poignant pathos for those working in occupations characterised by volatility and the heightening of an already precarious existence. Still, Kupa speaks of friendship and camaraderie - the kinship of miners, who migrated from their communities in rural areas to densely populated urban cities, in search of better livelihoods. To Kupa, there is a solidarity that exists underground and in the shifting.Mine artists not only depicted conditions underground, but also the positive and negative impacts the mining industry had on the land and the community. The mining industry, although providing a source of income for many skilled manual labourers, is an industry that has a profound carbon footprint as it disrupts the natural functioning of ecosystems, by causing water contamination, soil erosion and a loss of biodiversity. In recognising the environmental harms of the mining industry, there is a need for ecological alternatives to extractive processes that would benefit both people and the planet.Art about land issues have become forms of creative land reclamation. To converse with the land is an act of making meaning and memory. To colonised peoples, the land is a site of identity and belonging, intermeshed with history and with heritage.Historically, land has been used as a tool of oppression when considering notions of accessibility that concerns which bodies are or are not denied entry. The topic of land ownership is influenced by government policies and public opinion on issues of resource extraction, technological advancement, and more recently, Indigenous sovereignty and ecological concerns about climate change.Kupa utilises the Italian painting technique of impasto to craft depthful small-scale works in which he layers Earth and figures of people. Kupa captures tonalities of dark and light, with his colour palette elevating the depth of his subject matter. Kupa’s works are a seamless merge of abstraction and figuration owed to softly sporadic flows of paint.Kupa’s subject matter and technical style are influenced by leading South African artists such as Ephraim Ngatane, Gerard Sekoto and George Pemba. These are artists who used visual mediums to speak on the injustice of racial inequality and depicted the vibrant yet politically charged realities of those living in townships during the apartheid regime in South Africa.As a contemporary of his influences, Kupa continues the significant contribution to the cultural development that emerged in 20th century South Africa, as his paintings capture the essence of what it means to be driven by the hope for opportunity. Kupa’s works are grounded in the memory of experiences originating in both past and present, while carrying the identity of the crowd and the spirit of the collective.

-

Andrew Ntshabele: Liminal Musings

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

In Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression Jacques Derrida refers to the “future interior of the archive”, which speaks about the archive as a mnemonic device that does not look back at history, but rather it is exceptionally futuristic. The archive determines what future generations will know, making it inherently ‘forward-looking’.

Andrew Ntshabele’s work is an expression of juxtaposed temporality and in reaching into the depths of the archive, his artistic practice is an endeavour of radical remembrance. The archive plays a significant role in the visualisation and remembrance of identity.

Andrew Ntshabele’s artworks function as a double disruption to the Western art canon – first through the undaunted insertion of Black figures on canvas, and secondly within gallery spaces that were often permeated with colonial imagery. Ntshabele actualises decolonisation as art practice through historical visual assemblages; hereby subverting narratives of erasure by foregrounding the young and the maternal, most notably the motif of the Black child and the Black mother who are often marginalised.

Ntshabele uses art to speak a poignant and authentic truth about the past, to and for the children and for those who have experienced oppression. Ntshabele’s art is birthed from spirit and prayer, deeply grounded in memory both personal and archival, yet bound by contemporary reflections that inspire a tender sense of hope. Ntshabele’s subject matter is not intended to cultivate division, but speaks of the need for a recognition of the past as a means of collective healing and reconciliation. -

Frans Thoka: We are the messiah

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

There are artist activists that utilise art as a cultural weapon of racial struggle and consider art as a way of transcending creativity toward a more political expression. These are the artists that often remind other creatives of their obligation to foster a revolutionary culture within society through art. Emerging contemporary African artist activist stands amongst these artists, through subject matter that grapples with injustice and imprisonment that is dually literal and metaphoric in the contexts of culture and spirit.Frans Thoka is an artist that advocates for historical reflection, for the addressing of generational trauma, for ancestral connection. For Thoka, art is purpose, a calling to speak the truth about that which cannot be forgotten. Thoka utilises art spaces to exhibit blanketed shadow landscapes that cast light on troubling tribulations in a country with a darkened history owed to multiple forms of oppression and racial erasure.In Discourse on Colonialism, a book described as a ‘poetics of anti-colonialism’ as a manifesto for the Third World, French poet, author and politician Aimé Césaire offers an in-depth critique of colonialism and its inherent contradictions. Colonialism, intricately linked to imperialism, was justified on the basis of Western progress. This “progress” was sought after at the expense of communities of colour. This was a “progress” saturated with mass racial subjugation, and violated human rights. Colonialism then is a subversion in and of itself, its own embedded ideals.

Frans Thoka laments that historically humans have not been quite humane; his artwork is thus a message that signals an urgent return to our lost collective humanity. In using a distinct art medium of blankets, Thoka emphasises that there is a need for a social imperative of softer realities, for existences that do not reside at societal margins.

The Westernisation of art emerges through the preservation of white history that has attributed sole validity to its own existence, at the expense of those racial and ethnic groups deemed as Other and subjected to otherness.Decolonisation has taken hold in public space, education, culture and art. Decolonisation is the process of ameliorating past socio-political injustices endured by former colonies through the struggles of redress and reclamation. Within an African context, decolonisation is a project of re-centring Africa and its people. It provides Africans with an opportunity to narrate African histories and experiences from an authentically African perspective.

Thoka artistically speaks about the remnants of the apartheid regime and colonialism that continue to reside within racially marginalised communities. Remnants that have impacted cultural consciousness, identity and the navigation of public space through time. The art practice of Thoka is therefore radically decolonial.

-

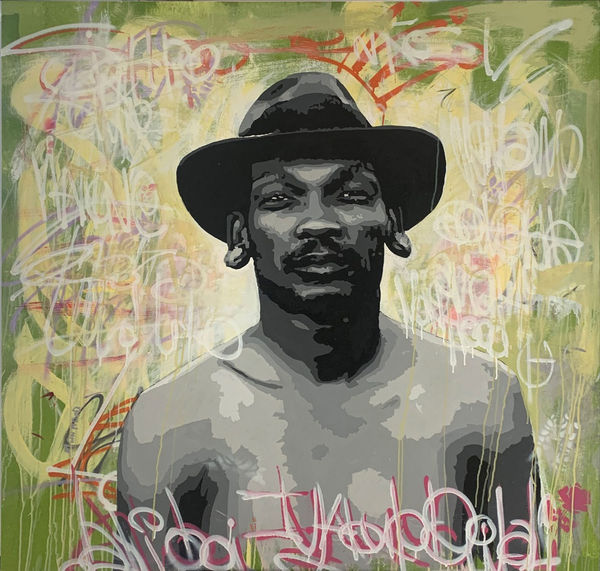

Ludumo Maqabuka: Subcultural Sites

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

Graffiti art merges street art and public art. It is a form of visual communication, often unsanctioned, to and for the public. It is a rebellious art movement that dates back to the ancient empires while also having its origins in 1970s New York. Graffiti has since grown in popularity, with multiple renowned artists incorporating the graffiti aesthetic into the work.Ludumo Maqabuka creates a seamless fusion between graffiti and figurative art in his personal interpretation of the complexities of South African society, notably an exploration of how social norms in Black townships communities are particularly shaped by urban subcultures.The term subculture is defined as a subset culture that occurs outside of a dominant mainstream culture. Subcultures are groups that have varying non-mainstream beliefs and interests, evident in an affinity for visual and material culture that is often considered as deviating from the mainstream. Mainstream culture exists on a continuum of inclusivity and exclusivity. When the interests and beliefs of marginalised groups are not represented by mainstream culture; a sense of belonging and freedom is then created through the liminality of subcultures.Contextually the development of subcultural theory can be credited to two perspectives, the Chicago School of America and the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) of Britain. In the context of subcultures, there have been two key observations. The first observation is that deviance and social circumstance tend to be interlocked, with marginalised groups, often gravitating toward subcultures. The second observation centres on the resistance that underpins subcultures, manifesting as a particular reaction against an existing social order. This resistance is often articulated through external personae such as sartorial choice and body modification.Popular culture is not high culture, but mass culture, it is an authentic culture of the people. As a form of mass culture, it is characterised by mass production and mass consumption. Hence, the integration of popular culture, as a form of mass culture, has posed questions about whether or not art has become more accessible to the broader public.

-

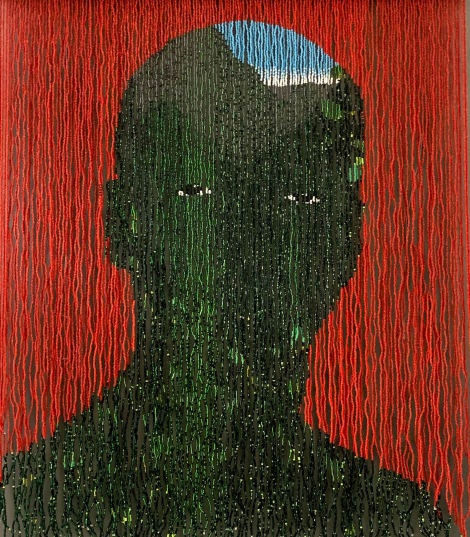

Morgan Mahape: Beaded Tradition

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

The art world has joined the conversation on sustainability. The pending question is whether environmental degradation and climate change can be addressed through the art scene. Sustainable art is often defined as either art that uses sustainable materials and art that encourages conversations about sustainability.Using beads as an art medium is an ode to the negation of value within African histories of trade and colonialism. In archeological history, beads and beadwork can be traced back to the dawn of civilization, but its source, its origin, is Africa. The technological age of the art form can be determined by the material used. African beads were predominantly made from organic materials such as bone, (egg) shells and seeds. Africa has traded beads with countries situated in both Asia and Europe, but it was European beads made from glass that became rather popular and prized on the continent. Across the world beads are adornments and carriers of meaning - communicating messages that are social and spiritual in nature. In Africa beads are important signifiers of culture and ethnicity which in part constitutes identity.Mahape weaves the individual to the community; his is a conscientious construction of a coming together that cannot be forsaken. Hence, a central thematic concern in the works of Mahape is that of community, in a global sense, but particularly in an African context.The connection between the community and the individual is emphasised by the philosophy of communitarianism. The philosophy offers a critique against the belief that development is solely gained from (rugged) individualism. Instead it posits that the social identity and personality of an individual is significantly shaped by relationships made within a community. In Western values, the individual is singular, while in Africa, the individual is defined according to the uniquely African ethos of Ubuntu which when translated means “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.”

-

Daniel Stompie: Prelude to Expression

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

The artworks of Daniel ‘Stompie’ Selibe embody the characteristics of Neo-Expressionism, a contemporary art movement that draws from themes of culture, mythology, history and even nationalism and the erotic.

Neo-Expressionism emerged in the 1970s, gaining popularity in the American and European artworlds in the 1980s, particularly Germany with its strong heritage of Expressionism. The art movement of Neo-Expressionism exists at the intersection of Modernism and Postmodernism and drew its influence from several distinct art movements, namely early 20th-century Expressionism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.

Daniel ‘Stompie’ Selibe forms creative novelty formed from deconstruction and then reconstruction of the existing. The details in Selibe’s artworks reveal diverse depth by design, as he brings the canvas to life through vivid colour and abstract mark-makings.The art genre of Neo-Expressionism is distinguished by a return to painterly figurative representations of, but not limited to, the human form that are often distorted, which in the process, seamlessly merges the styles of figuration and abstraction. Neo-Expressionism stands in reaction, according to Sotheby’s to “detached intellectualism and ideological purity of Minimalism and Conceptualism.”The textural works of the Neo-Expressionist art genre are often considered to be violently emotive, capturing intense inner emotions and subjective perceptions of reality and ideas. The art movement sought to shift away from realism and non-representational to embody more expressionist art forms. Hence Neo-Expressionist artists, most notably which include Jean-Michel Basquiat, Anselm Kiefer, Enzo Cucchi, Julian Schnabel and the founder of the movement, Georg Baselitz, and many more, had multiple cultural names across the world such as ‘Neue Wilden’ (‘New Fauves’, derived from Fauvism) in Germany, ‘Transavanguardia’ (Transavantgarde) in Italy, and ‘Figuration Libre’ in France. -

Carey Carter: Earth Muse

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

Carey Carter uses materiality as language to carry a critical ethos of environmental sustainability. Carter’s artistic practice is an act of ancient remembrance that foregrounds the importance of ethical co-existence with the more-than-human world. Symbolically Carter’s sculptures are a reminder of our corporeality, that is to have a body and be a body, is what brings us closer, it is our source of connection to humans and non-human embodied others.The nature/culture dualism has resulted in the current geological epoch of the Anthropocene, characterised by ecocides and an urgent climate crisis. Algerian-French philosopher Jacques Derrida revealed that dualisms may appear to be symmetrical when in actual fact they are implicated in profound power relations, whereby the dominance of one construct is dependent on the subservience of the other. In this case, the human species have predicated cultural dominance at the expense of the natural environment, however, the dualism of nature/culture can no longer hold, for the survival of all species is dependent on bridging this separation.The discourse of New Materialism advocates that bridging the nature/culture separation must begin with a radical return to matter. It must begin with language. To Social Constructionists language lacks neutrality, for realities are constructed by language; worlds are created through processes of description. Hence, a significant emphasis is placed on constructing a new terminology in order to reconfigure the relationship between humans and the more-than-human world, as an imperative act of care. American Professor and Feminist New Materialist scholar Donna Haraway coined the term “semiotic-material knot” that speaks about the intricate entanglement of language and the material world. For New Materialists, the notion of '‘wording’ is ‘worlding’' is the locus of world creation, in which the usage of language determines how worlds are treated.Visual artists are increasingly illuminating an innate connectivity and mutual interdependence that exists between human and more-than-human ecologies. These are artists that are not only engaging with but are creating artistic productions as creative strategies to bring awareness to questions surrounding what it means to be human and what positions humans and non-humans hold in the Anthropocene.Carey Carter is one such visual artist who engages with the Earth to source natural materials in order to create her organic sculptures which are in turn interwoven with the physical and metaphoric substance of all materials occurring in nature. The sculptural forms of Carey Carter repeatedly pointed to the continuity of Earth and the human body.

-

Fathema Bemath: Material as Metaphor

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

Fathema Bemath uses clay as the material from which to sculpt her sculptures. Like clay that can be moulded, so too are women moulded by the norms and expectations of a patriarchal society. As her clay sculptures fracture, so do women fracture under the pressure of conforming to the ideals of femininity and beauty. To Fathema, the material carries her message of liberation for all those who identify as women. Hers is a message that recognises that injustices done to women, can as a start, be remedied through artistic dialogue and by an unapologetic sense of being that is not defined nor restricted by the gender binary and gender social constructs.Beauty standards have changed gradually through time but contemporary women artists, particularly artists of colour have used multiple mediums in art to assess and challenge those depictions of beauty that have equally remained unchanged. South African sculptor Fathema Bemath is one such artist that has critiqued and challenged ideal standards of beauty held by men and the West by advocating for the need to embrace diverse forms of beauty.Minority groups have often been subjected to prejudiced representations which must often be addressed by artists within those minority groups in order to insert and assert the voices and experiences of their respective communities.Fathema Bemath uses the female perspective and female subjectivity to represent the bodies and beauty of women differently through sculpture. In this sense Bemath utilises sculptures to foster identification and mutual recognition between the viewer and sculpted subject. Hence Bemath’s sculptures function as a synecdoche, in which a part represents the whole – in this instance, the larger community of women from a variety of backgrounds.Bemath deviates from portraiture to foster an all-encompassing engagement from multiple angles with her sculptural female forms and thus with women. In doing so, Bemath challenges the male gaze to disrupt the objectification and stereotypical over-sexualisation of women in creative spaces such as galleries and museums.The famous notion of ‘the male gaze’ was first introduced by the discipline of Psychoanalysis. Laura Mulvey’s conceptualisation of the Freudian term ‘scopophilia’ refers to the pleasure of looking, in addition to the pleasure of being looked at. Mulvey presented a related feminist critique of the male gaze and its association with a masculine subject position of voyeurism and narcissism in her seminal article titled ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975).Agency is a primary tool in the politics of visibility for marginalised groups. The possibility to reclaim agency arises when the male gaze can be manipulated despite the presence of those structures of domination that aim to maintain it. Therefore, in relations of power, those who have been deemed as subordinate have learnt through experience about the critical (female) gaze as a gaze that is oppositional. The female gaze is a self-conscious act that not only disorientates the male gaze but responds to hegemonic looking-relations that are gendered, racial and cultural in nature. The female gaze is a gaze that rises above the depiction of women as always the victim of the gaze, by alienating the subject, who is generally male and/or white, who has always had the privilege to gaze freely.

1. Ahmed, S. 2016. An Affinity for Hammers. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 3(1-2):22-34.

-

Karen Cullinan: Experiential Encounters

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -

The concept of phenomenology, coined by Austrian-German philosopher Edmund Hursell, considers the philosophies of the subjective lived experience of the individual. Multiple forms of visual culture have become tools for inquiries of transcendental phenomenology, at first to elucidate the nexus between the visible and invisible as metaphors for the conscious and subconscious, and secondly to capture aesthetic “expressions of human life” as stated by German philosopher Martin Heideggar.

The artworks of Karen Cullinan are phenomenological in nature, as she probes at time bound subjective human experience that carries philosophical implications of the human condition, that when deconstructed, could even possibly allude to subtle universal truths.

Linked to phenomenology is the notion of 'situated knowledge’ coined by feminist New Materialist scholar Donna Haraway. Situated knowledge speaks about knowledge that emerges from your living body as a living being, hereby recognising the link between meanings and bodies. The term holds that knowledge is obtained subjectively from experience and that there cannot be a splitting of subject from object. In this sense, detachment becomes an illusion, for living beings are situated in their bodies which are situated in spatial or temporal contexts.

American physicist and feminist theorist Karen Barad captures the essence of situated knowledge, writing that “we are not outside observers of the world. Neither are we simply located at particular places in the world; rather, we are part of the world in its ongoing intra-activity.”

Karen Cullinan creates art that emerges from her knowledge, her own being. She engages in the manifesting of her inner world in varied visual mediums. Cullinan’s artistic process is cathartic and she uses a canvas and other mixed media as sites on which the source of her transformation is translated. Cullinan creates works that are a documentation of her personal odyssey through life, evolving and shifting through time as she is, hereby remaining in a constant condition of becoming.

1. Haraway, D. 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3):575-599.2. Barad, K. 2003. Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Signs, 28(3): 801-831. -

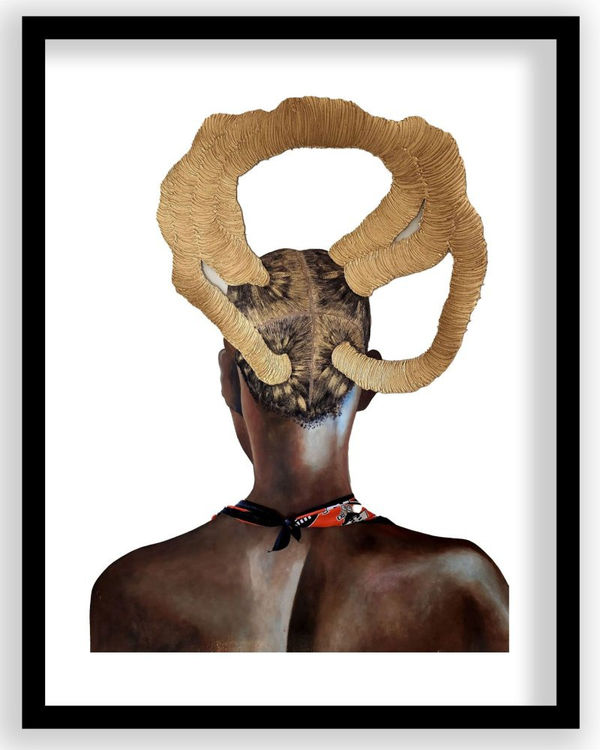

Samantha Maseko: Crowning Glory

AN ESSAY BY KEISHA JACOBS -