The new group show at Artyli – Whispers in Matter – is a reminder that art is about feeling. All our senses are triggered. Touch meets sight … smell meets sound. The sum of our truth is the sum of our senses. Even the mind, mistakenly considered to be Reason’s chapel, is a sensory and intuitive organ. It is not the ‘Empire of Signs’ that matters but the Emporia of the Senses.

It is unsurprising that the curatorial vision veers towards abstraction, and finds the figurative inside of it. In his manifesto on abstraction, Jerry Saltz discovers an enchanted realm, art as a visionary tool – the best ‘ever invented by human beings to imagine, decipher, and depict the world’. For ‘abstraction not only explores consciousness – it changes it’. This is because abstraction, or art more generally, is not as objectifiable as we would like to think. Rather, art ‘exists in the interstices between the ideal and the real’, between projection and sensation. This is because, above all else, it is a sensuous expression, no matter how chilling, how warm. What one connects with when one listen, tracks, navigates, or inhabits an artwork is ourselves. Art is elemental, it is earth, water, sky. It is we who become a divining rod.

Talia Goldsmith’s series ‘Singing Roots’ is a love-song to listening and to making. Inspired by memory, which is none other than instinct, she notes, on completing a sculpture, that it is she who was now embraced ‘in their harmony’. The making of art completes one, it momentarily makes one whole again. It was then that she realized that her grandmother’s song had accompanied her throughout the creative process – ‘Each sculpture in tune with its internal voice. Each sculpture a singing root. Each sculpture bearing witness that I did listen’.

Another sculptor, Robert Wagener, too finds solace in the process of making his ceramic forms which, for him, evoke ‘the volcanic origins of the earth itself’. It is the grounded nature of Earth that is the artist’s creative forge. His thickly stratified forms speak of a ‘deep time’ which, for Robert Macfarlane, evokes the rich density of existence. Clay, made of earth and water, is the most primal source of human creation – a reminder that we too are made of the same matter – for the earth’s cycle is ‘dynamic’. ‘Mineral becomes animal becomes rock; rock that will in time – in deep time – eventually supply the calcium carbonate out of which new organisms will build their bodies, thereby re-nourishing the same cycle into being again’. Matter is never inanimate. Never truly silent.

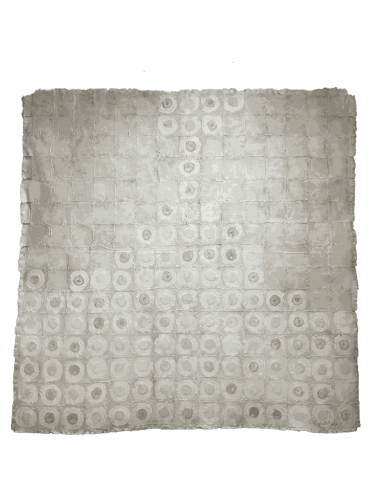

If art requires a listening ear and a sonorous heart, it is because it is life. Or, as the sculptor Louis Bourgeois eloquently phrases it – ‘Art, no less than wisdom, waits on life’. Art exists because we are alive. Art exists in and through human life through all eternity. It is this synergy that is the core of Toni-Ann Ballenden’s relief works. Almost geological in the impression they yield, seemingly akin to fossilized remains, they echo Macfarlane’s notion of deep time. The earth is a gestating secret which those, who are able, can reveal to us. Ballenden is such an artist. A conjurer, a seer, she unlocks and unriddles, then plunges us back into an enigma. This is because the world’s wonder can never be wholly revealed. Her art is a mantra, it is talismanic. As such it requires only that we share a mystery. Trace elements abound … gnomic residue….

Raja Oshi shares this elemental preoccupation. Like Goldsmith, Wagener, and Ballenden, Oshi is drawn to earthen tonalities, earthen mysteries. Her bodies are shadows on a cave wall, her geometry is ancient. In joining the human and abstract realms – in reminding us that they are indissoluble – Oshi returns us to a humanity that long predates the eighteenth-century Enlightenment ideal, the self-fulfilling fantasy of rationality, power, and control. Instead, we are returned to more durable intimacies, to an ancient order, an ancient love. As the Greek philosopher, Pythagoras, reminds us – ‘Geometry is knowledge of the eternally existent. Number is the within of all things. There is geometry in the humming of the strings. Time is the soul of this world’.

Once again, we return to whispers in matter – the geometry of sound … the soul that lies inside of things. ‘Souls are mixed with things; things with souls’, the anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, reminds us in The Gift. This is because of the sacramental nature of life, how we honour our lives and the lives of others through creation. It is not vain for Wagener to conceive of a ‘successful’ sculpture startling the viewer, to wish that his creation ‘draws them in and ultimately never lets go’. For despite the transitory nature of life, and the longed-for eternality of things, the hope for the endurance of the things we call art, through love, is an all-too-human goal.

Like Raja Oshi, Daniel Chimurure also conceives of art as an incarnation and a ghosting – as a trace element. Toni-Ann Ballenden also shares this perspective, though hers is more primordial. Chimurure’s ghost-world is more immediately present. A combine of raw collage and paint, the world Chimurure evokes is as abstract as it is suggestively figurative. The works are illumined yet not, despite the peculiar presence of an abnormally large light fitting or globe. Once again, we are returned to Plato’s shadowy figures reflected on a cave wall, though in Chimurure’s case, unlike Oshi’s, there is no sacramental sustaining union. Desolation creeps in … isolation too. We are perhaps caught in the pathos of loss. Is it true, as Kurt Cobain remarked, that ‘all alone is all we are’? Or is Chimurure not also helping us to find companionship in our loneliness, or aloneness? Is love the great and most enduring whisper?

Hussein Salim and Lynette van Tonder, by way of comparison, share a passion for colour – though here we should acknowledge colour’s tentative presence in Chimurure’s art. In Van Tonder’s works the delineation, however, is much stronger, the artist inviting us into boldly rendered cartographies in which people and places – being and space – are enmeshed. Density is the key to Van Tonder’s creative expression. Sometimes that density is becalmed, on other occasions it’s a maelstrom. The mood-shifts are vital. For her, questing is the driving force – be it a quest for self or a quest for community. That this occurs inside a ‘grid’ is a reminder that chaos requires order, that error requires grace, and that Van Tonder’s art, no matter how turbulent, requires a ‘course correction’.

Are artists the mapmakers of the soul? Are they our guides into higher and nether worlds? Do we long to be taken on unbidden journeys? Is that why art – especially art that is not easily decipherable – our greatest elixir? Why else would it draw us so deeply inward, before expelling us? Why would it sound its siren song, whisper its enchantments? Perhaps because, as ‘the greatest visionary tools ever invented by human beings’ it allows us ‘to imagine, decipher, and depict the world’ – to read it as a scroll, some cypher, some uniquely compelling riddle. Therefore, if this exhibition matters, it is because it allows us to enter the portal of our choice, for in life, if we are not beckoned, we fear that we do not exist.

Hussein Salim captures the pathos built into the creation of art. ‘For me, art not only evokes memories and contemplation of the loss of home but it also encounters the present and shapes the future’. It is the entire creative arc that Salim evoke. If loss is inescapable, so is yearning. Nothing truly dies, all of life is regenerative. This is Robert Macfarlane’s point in his book, Underland, and it is also the vital point expressed by every artist in this exhibition. Salim’s expression thereof is eloquently subtle, even quiet. We enter gentle worlds in which light and shade dance about, in which worlds hover as much as they recede. We are buoyed, held aloft, carried. At no point are we ever lost in a painting by Salim. Unlike Van Tonder, he navigates us through the world without a discernible grid. We travel blind … intuitively. Though this core orientation, this means of moving through the world, is also the lesson expressed by all the artists. Some may need a more organized system, others not, but all, in their different ways, invite us kindly, gently, into realms ultimately trackless, with no finite spoor. We need some light to carry us along … some inner light, some thrumming soul, some fathomless longing.