-

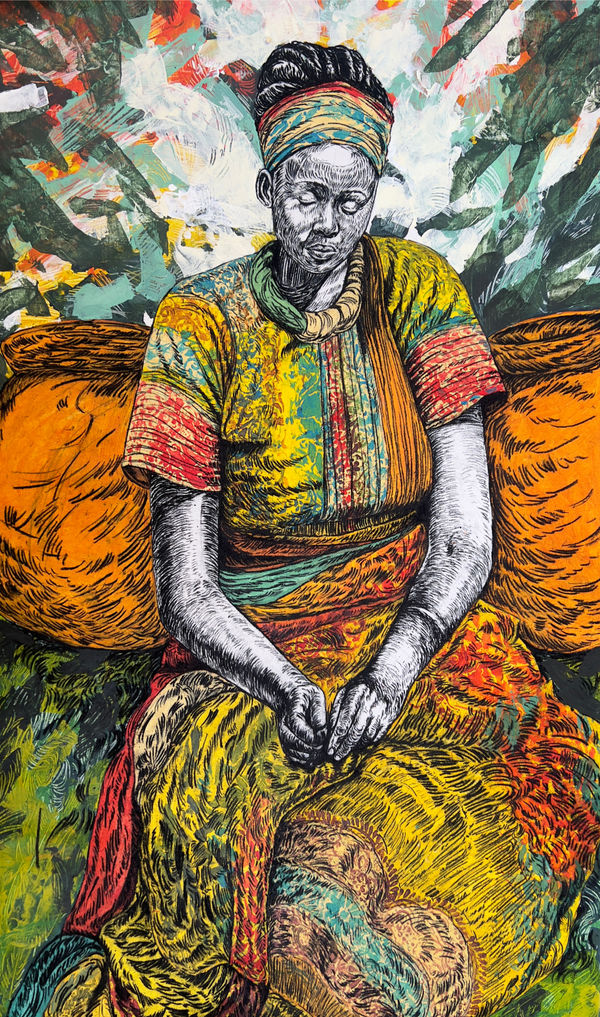

Q: I read that your works are situated within the art movement of realism, what are thoughts on this?A: Many of the works that I produce, if not all of them, are inspired by my own personal experiences - whether that is my upbringing in a township setting or in a rural environment. I grew up in a culturally rich household where the primary language spoken was my home language, Tshivenda. My family made it a point that whenever there was an opportunity to return to the village, we would do so. These repeated returns and exposures allowed me to appreciate the small things in life, the overlooked moments and the everyday gestures. The village where I spent much of my childhood is, and still is, a vast land filled with meaningful encounters. When it comes to the idea of realism in my work, it is not necessarily about technical realism alone, but rather about depicting people engaged in their everyday duties, in a way that is similar to Gustav Courbet’s understanding of realism. It is about showing people who are harvesting their crops, eating from their land, sustaining themselves through what their environment offers. These daily acts of survival, care, and community are what inspire much of the work that I create.

There is also an element of spirituality that I am weaving into the narrative within the body of my work. This spiritual layer feels necessary because when you are living in those contexts, that is rural spaces or townships, spirituality is often a way of seeing and understanding the world. It becomes a thread that connects the physical acts of daily life with deeper meanings, beliefs, and ways of sustaining hope. Not only is spirituality a pivotal part of my narrative, but so are the oral traditions that were passed down from generation to generation. These stories, proverbs, and shared memories carry our history, our heritage, and our informal education. They shape how we see ourselves and how we relate to our environment and to each other. By weaving these elements into my work, I am acknowledging and preserving that cultural wisdom in visual form.

Q: Your artworks feature portraits of the man and woman in township and rural areas. Would you say the intention of your subject matter is to shift these communities from the margins?A: The whole idea behind the work that I produce is not necessarily to talk about specific cultures, but rather to speak about culture in the most ubiquitous way possible. It is about the human experience, rather than about defining or confining it to one community. The reason behind the figurative representation, whereby the men sometimes appear feminine, or the women embody more masculine traits, is because I am not trying to reinforce or blur the lines of any social construct. I am simply depicting people as they are, without labels or rigid identities. While these figures are inspired by people I am personally connected with, they are not portraits of specific individuals or genders. They are more like vessels for a universal idea of humanness. Hence, I would not say that the intention is strictly about shifting communities from the margins. It is more about creating an idea of oneness, an almost utopian idea, where these people remain grounded in their own understanding of life. Through listening to poems, stories, and oral traditions, I have realized that these communities were never as marginalized in spirit as they might have been made out to be. They were strong, wise, and deeply connected to their environment. By depicting them, I aim to immortalize their existence and their way of living. In today’s context, many of these values and ways of seeing the world are overlooked or undervalued, but they have sustained people for generations. Through my work, I want to highlight and honour those things, to remind us of what we are drifting away from, and what still holds power and meaning.

Q: I read that themes in your work centre around identity, memory, and the environment in terms of the spaces humans inhabit. Can you please expand on all three of these themes?A: When I speak about identity in my work, it really comes from my upbringing in Pelindaba, or Soulsville, which is a township that became a melting pot of different cultures. People came from various homelands and settled together in Pretoria, building a community even though they did not all share the same roots. My neighbour was Zulu, across from us was Tsonga, behind us was Pedi, and we were Venda. Living side by side like that affected how we understood the world and how we understood ourselves. It shaped identity in a way that was not fixed to one culture but rather woven from many, in the way we listened to music, danced together, shared and tasted each other’s food. Over time, the rigid idea of “identity” dissolved; it became about being human, about shared existence rather than fixed labels. That fluid sense of identity is what I try to capture in my work.

Memory is another theme that runs deeply through my practice. A lot of my work speaks from a place of nostalgia. Many of the people who shaped me, my grandparents especially, have already transitioned, but their presence is always with me when I create. The moments I shared with them, the warmth and lessons they left behind, live on in the work. For me, each piece is like a feeling made visible, a way of cherishing memories that last far longer than we do. I believe it is those moments that shape who we become, so I try to honour them through my brushwork and storytelling.Then there is the theme of environment. I grew up moving between vast rural landscapes and dense township streets. When I was in the village, I would wake up early and follow my grandfather to his farm up on a mountain. We would leave at dawn and sometimes not come back until evening, or he would take lunch with him and stay out there all day. I remember just looking at those rolling hills, those lumps of land that felt almost unreal to me as a child. When we returned to the township, that open space was replaced with buildings, so there has always been this contrast in my mind between nature and the built environment. My work does not try to pit them against each other but rather acknowledges how they coexist, how people adapt and find meaning within both. It is about showing how the spaces we inhabit, whether vast fields or tight streets, shape who we are and how we live.

Q: What message would you like your work to convey when it is viewed?A: Honestly speaking, when my work is viewed, I do not really expect much. I am of the belief that the greatest satisfaction or success for an artist is achieved in the making, because at least I am in control of that. When the work is done, it is done. By the time it is seen by others, it becomes an offering. There are no expectations attached to how people should respond. I just hope that whoever stands in front of it resonates with the story in some way. I hope they feel something, whatever that feeling may be for them. That, for me, is enough.

Q: Your brushwork and sketch work is reminiscent of a Post-Impressionist style, which artists would you say inspire your work?A: I was introduced to a wide range of styles, movements, and practices by my mentors and educators, from the theory to the actual making. I have always appreciated the works of Vincent van Gogh. I admire him greatly, though I would not say he directly influences what I create today. I also have a deep respect for Caravaggio. I am fascinated by the scale of his works and how he was probably one of the first realists through the way in which he portrayed biblical stories using everyday people. He placed ordinary people on a pedestal, portraying them as sacred and righteous. His dramatic use of light and darkness, referred to as ‘chiaroscuro’, and that tension of realism inspires me a lot. The same can be said for Rembrandt and Peter Paul Rubens. I appreciate how Rubens, for instance, used people from his own circle and how his line work and brushwork pushed the boundaries of naturalism.However, as a South African artist, I cannot ignore the roots of our own visual heritage. Mark-making soothes my soul. It feels instinctive and right because it draws from our rock paintings and San art, where marks, or rather symbols, were telling stories long before we put them on canvas. Those stories, often about spirituality, resonate with my own work. For example, in ancient rock art, the longer the figure’s physique, the more spiritual or sacred the being. That symbolism really influences how I stretch or distort the human form in my paintings. I am also inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, like the works of Hokusai. I love how proportion is handled, not perfectly, but intentionally human and expressive. The use of color, textile, and layered patterns creates an immersive world that pulls you in. All of these influences come together in my work, from Post-Impressionistic landscapes and expressive brushwork, to the deep marks and symbolic figures rooted in my own cultural heritage.

Q: Your medium is a combination of charcoal and paint. What is the reason for this choice?A: Charcoal, for me, is deeply tied to my most humble experiences. It reminds me of my grandparents, of my land, of the simple moments that shaped who I am. The charcoal I use is not always the processed kind you would purchase in a store. It is often charcoal that comes straight from burnt wood, the same charcoal used to make fire in many rural homes. Using it connects me directly to those memories and to the everyday life I am trying to honour in my work. Charcoal is also very delicate - a simple sigh while I am working can completely ruin the details. So I really have to pay attention. Sometimes the room needs to be quiet, sometimes it can be chaotic. Either way, the work still has to be made, but I have to be present. It puts me in a meditative state - some people call it flow, but for me, charcoal is humbling because it reminds me that the process requires care and patience. I use paint because I love colour. Colour has always been a big part of my life and culture. If you look at traditional Venda cloth, it is vibrant and bold, full of rich, bright colours. Even in my village, the landscape was alive with so many shades of green and bursts of natural colour. That shaped the way I see the world - as vibrant, layered, full of tones that deserve to be celebrated.

The different mediums I use are also an indication of my love for art itself. I do not want to limit myself to just one material or one way of making. Many of the artists who still inspire me were not just masters of a single medium, but rather that they explored everything. They understood many ways of creating, experimenting, and combining techniques. Hence, for me, mixing charcoal and paint, and whatever else I may choose, is my way of staying open, curious, and true to that spirit of exploration.Q: You mentioned that you were studying Law while pursuing your art career.What prompted you to choose Law as a field of study?A: It was a safer option, really, that is the truth. Studying Law felt like a secure path, something steady to fall back on. It is the kind of choice many families hope for because it offers financial stability and respect in society. But if I’m being honest, art has always been a calling for me. It is something I feel deeply connected to, in a way that Law could never match. I do not feel any regret about studying law (well I did not finish), because it gave me structure and taught me to think critically. However, at the end of the day, I am more connected to my art than anything else. It is where I feel the most honest, the most myself.Q: When visiting your studio, I saw sketches on A4 paper - replicas of the finished works. Can you explain your artistic process?A: I would say that my process is very intuitive. Sometimes it starts with a photograph, sometimes with a memory, and often it is a collaboration between the two, mixing real references with what I remember or feel. But for me, it is important to begin with ideas first, because that turns the act of making into a real process. It reinforces the need to not rush. The work itself is already time-consuming, but taking time to sketch and plan gives it even more potency. The A4 sketches you saw in my studio are like anchors. They help me hold onto elements of the original idea. It is my way of preserving the essence of a piece before it becomes something bigger. Sketching also helps me let go. Some works I feel deeply connected to. It can be hard to part with them, but having the sketches makes it easier. It is like telling the work, “It is okay, you can go now. I still have your seed, your first form.” That is how I see it.

Q: You said that your mother is responsible for you being an artist and in many of your works, she is the subject. Can you elaborate on the ways in which your mother has inspired your creativity?A: Growing up in a township, the environment was not always safe. My mother knew that, and instead of simply telling me to stay inside or not to go out and play, she found a gentle way to keep me occupied. She noticed early on that I had a liking for creating art. Every Friday, which was really the only time I was allowed to go out, since weekends were when we had free time, I would ask her, “Mother, may I please go out and play?”, and she would say, “Yes, you can, but first, go grab a piece of paper and draw something.” Before I knew it, I would be sitting there, filling page after page, sometimes ten pages or more, and by the time I was done, the sun would have gone down, and it was too late to go out. She used that little tactic until I was old enough to be more responsible. One day, she told me that she always encouraged it because she realized I had a gift, but also because she knew it kept me safe. It kept me out of trouble and away from some of the dangers that can come with township life. Over time, it became a habit. Even when I was allowed to go out, I would find myself thinking, “Let me draw something first.” She was very intentional about nurturing that side of me, so much so that she even looked for an art-focused high school in Pretoria, which is how I ended up at Pro Arte Alphen Park. I do not think she ever imagined that I would truly become an artist. I think that surprised her. After high school, she said, “Okay, now that you’re done with the art stuff, go pursue something more serious.” So when I chose to continue with art, it was a bit of a culture shock for her, because where we come from, art was never really seen as an obvious or practical choice for an occupation.

Using women as a reference in my work is my way of appreciating their resilience, their strength and what they stand for. Women, for me, hold families and communities together, often quietly and without recognition. By making them the subject of my work, it becomes a tribute not only to my mother but to all women who carry so much yet remain pillars of hope, strength, and life.

Q: When visiting your studio, there were some experimental artworks with collage that you were working on. Can you share more about the theme of your emerging body of work?A: I think the story only continues. It only deepens as the narrative is told. For me, that is the nature of this work: it keeps unfolding. There are definitely ideas in the works, but I do feel that talking too much about things that have not yet fully taken shape yet can take away from some of their magic. Some things need time and space to grow quietly before they are shared with the world. So I believe that when the time is right, communication around the new work will start to emerge. Until then, I trust the story will keep expanding in its own way.