-

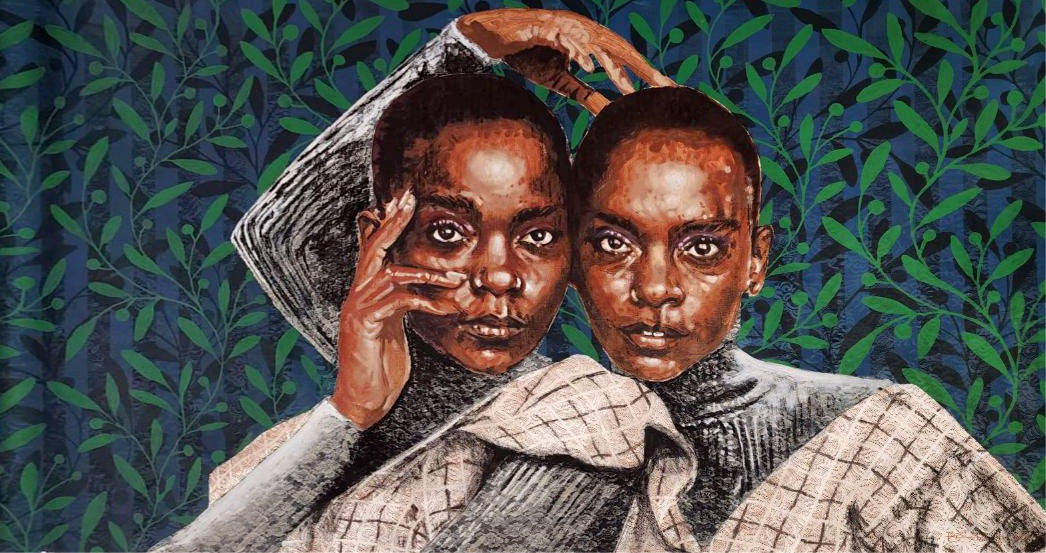

Q: Your work centres around the spirit of ‘Ubuntu Ngabantu’, a term deriving from Zulu philosophy and translating roughly into ‘I am what I am because of who we all are’. Why have you chosen this particular theme for your work?A: Growing up in a township, there is a saying that a child is raised in a community by the community or the nation; it is never the job of one person. I became what I am because of the next person. Before I used to speak about issues that women face and when I chose the Zulu philosophy, which started during the period of apartheid, I started to talk about men. One of the things I wanted to touch on was the absence of men. When I was doing my research, it took me back to the earlier days when men left rural areas and went to the city (Johannesburg) to work in the mining industry during the gold rush period. I looked at what kept these miners alive away from home and looked at their living conditions and despite the circumstances, they used to have a spirit of Ubuntu as we call it today. They had more of a sense of community and an understanding of what it means to live together. During that period there were no cell phones or cell phones were too expensive to afford, so the main things they used as a source of communication were radios and letters. Letters took forever to arrive but radios, although not necessarily quick or reliable, was a form of communication they relied on. There were channels on the radio, for example Nkosi FM, that had programs about weddings and funerals and people from rural areas would call into the station to announce news for people in the city. Now you can imagine these men, maybe 12 or 20 of them sitting in a room and then getting a message via the radio that someone from their community or family had passed on. So these men had a way of caring for one another under difficult conditions. For me, this really defined ‘Ubuntu Ngabantu’. These miners came from all parts of the country, if not the African continent, each speaking different languages but they had a way of respecting one another. They came up with a language that accommodated everyone, irrespective of background and tribe. They became one, they became the slogan of ‘Ubuntu Ngabantu’ and I saw that spirit within them.

-

Q: There was a period when you were drawn to social realism (such as the work of Francisco Goya and the social allegories of Hogarth). Can you explain the intrigue with this particular art style, art movement?A: I have always been very strong when it comes to the technical part of art. I find it very challenging to even explain my work or build up a strong concept. During the period when I studied Goya, what attracted me was the composition, the colour, the perspective, the strong etched lines and how he defined struggle through dark and light tones. It was how someone like Goya would express a mood. That was most important to me. I actually focused on Diane Victor more than Goya and Hogarth, but each of them became part of what I wanted to do and depict. They became part of what made sense even though I studied their images more than their concepts.I never thought I would have spoken about social issues from the beginning. As someone who wants to make a living out of art, social issues are one of the most difficult ideas or concepts to sell. People do not want to wake up and see a social issue on their wall, they would rather want to see a beautiful work of flowers or sunsets. At the same time of wanting to sell your work, you want to address certain issues that are happening around you. As I was doing my third year, there was a push to speak about social issues, so for me, I wanted to address what was happening in my community at home, my surroundings. Not just showing the issues that I am exposed to but also coming up with solutions. As I was exploring social issues, I went out and interviewed people in my community and I got different stories from different people. It is not like the country is not aware of its own social issues, and people have been bringing awareness to social issues with music, but I thought that I would do it in a visual form. I had to find a way to package my work in a beautiful way where clients would not focus on the negative part of the social issues itself. I remember while I was still studying at Benoni Technical College, I did graphic design and one of the things I was taught was how to package a product. I used that idea of packaging a product because people buy the cover instead of the actual content. People are attracted to the outer shell. I wanted to force people to respond to social issues in a certain way within a larger community - showing my world and what affects us on the other side in a beautiful way.Before I won the ABSA Gerard Sekoto Award, I had spent time with Dr Paul Balis and one of the questions I asked him was how is he able to respond to my social issues, how does he interpret my work and how does the work make him feel and I realised that one of the biggest problems is that some people who are buying my work have never been to the townships and they were never directly exposed to certain struggles, so they are not equipped to respond to my work. So I challenged him to go to the township because 70% of the people entering the competition are young Black people from the township. For the artists entering the competition to be judged fairly and for the audience to be open-minded to their stories, they need to know where the artists come from, because if you as the audience are not exposed to these township areas, it is difficult to understand what we, who are from there, are talking about.

-

-

-

Your work often depicts how families survive poverty, unemployment, and other hardships. I have two questions in relation to this.

- Q: In what way can art facilitate conversations around the struggle for social security?

A: Art is a very powerful tool, yet over the years, we have been failing to teach people about it, especially in the Black community, we do not get support from the local areas that we come from. People are not educated or informed about art. So it is not an easy tool to use either. Art has been something that has been explored mostly by the fortunate or wealthy. When selling a painting, you have to consider that not everyone can afford to buy art, because it is a piece of luxury, so it is not for everyone. We are already addressing such things, through art programs, but it is limited because the right people do not go to township areas and also our environment does not allow a lot of people to easily blend in within our communities. What counts is education and a safe environment because that is what makes people go to certain areas. There is a gallery called Black Ink. The idea for this gallery was to create a platform to expose township people to the art market at large and create opportunities for our people.- Q: In what way can art allow the marginalised to reclaim their lost sense of dignity?

A: I can assure you that art gives hope to marginalised people. I once did a portfolio on the mining industry that formed part of an exhibition I think I did with Everard Read. I did a series of paintings about men living their dreams in a visual form. While I was interviewing these men, a lot came up about what is happening in the mining industry. So I asked them what they wanted to be, what their dreams were and I was surprised that many of them did not want to work in the mining industry, rather it was simply an opportunity that presented itself. That is when I got the idea to actually paint them in the occupations they wanted to be in. It was a really emotional portfolio of work, because I wanted to visualise them as what they wanted to be. When the exhibition opened, I felt like these men could see themselves in the way I portrayed them, even though their dreams were not happening or might never happen. To me, that is hope. It gave them hope of a better tomorrow; they could see their dreams happening for the next generation and the possibility of reaching goals.

I was invited to Zimbabwe to do an art project with a friend. We did a paper prayer project where we were dealing with children who were victims of various kinds of abuse. There was a group of young children there, mainly girls between the ages of 6 until 14, and you can imagine it was not an easy project, for us and for them to open up about what happened to them. So we took plain canvas and material that the children could use and told them to paint their stories and what affects them. It was asking children to express their emotions onto a canvas and you would have been surprised about how many stories came forward. I remember one time when I was watching a TEDTalk and the host said that we need to go back to basics - the real creative side of ourselves as adults, because as children we are the most creative - we do not question too much, we just express exactly what we want to say.So art works really well as a tool that gives back hope and light, to express emotions and helps people to open up. When people walk into galleries or art institutions, they see work on the wall, and most of the time, they are drawn to pieces that remind them of something, that makes them think about possibilities of being or achieving something more. So I would say art gives dignity back, if I am just thinking of my experiences and the social projects I have worked on. -

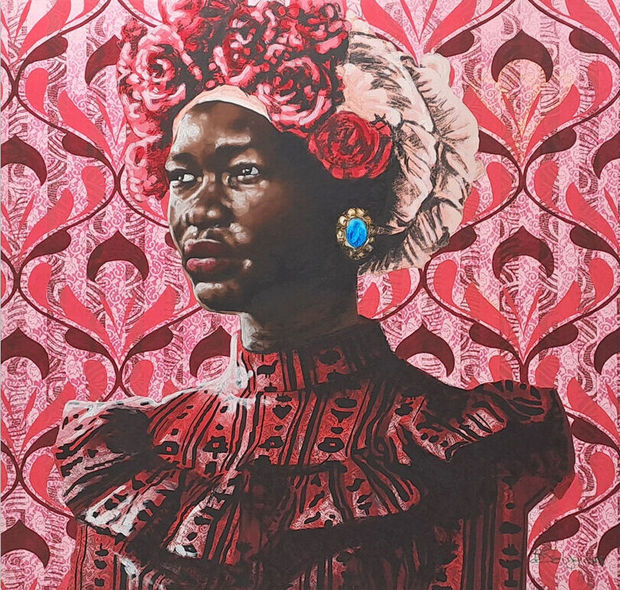

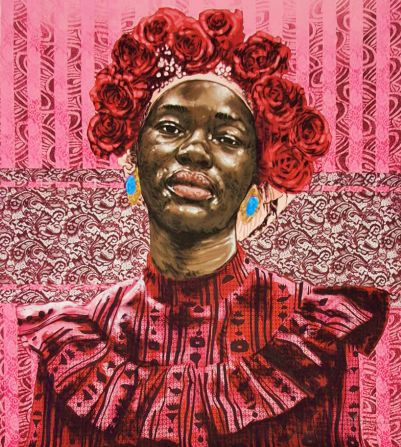

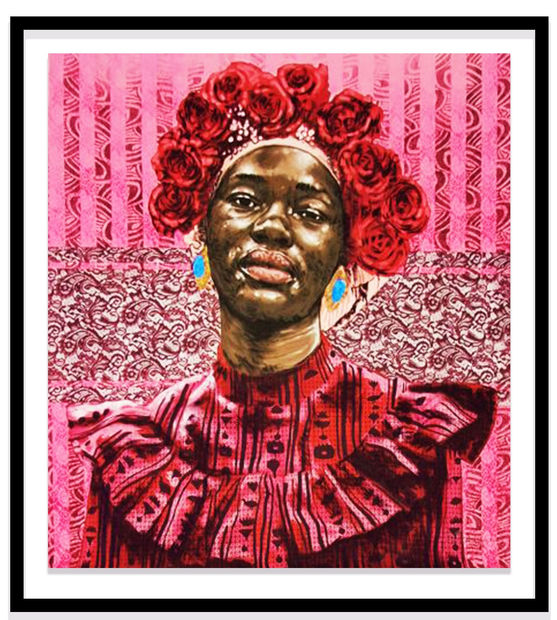

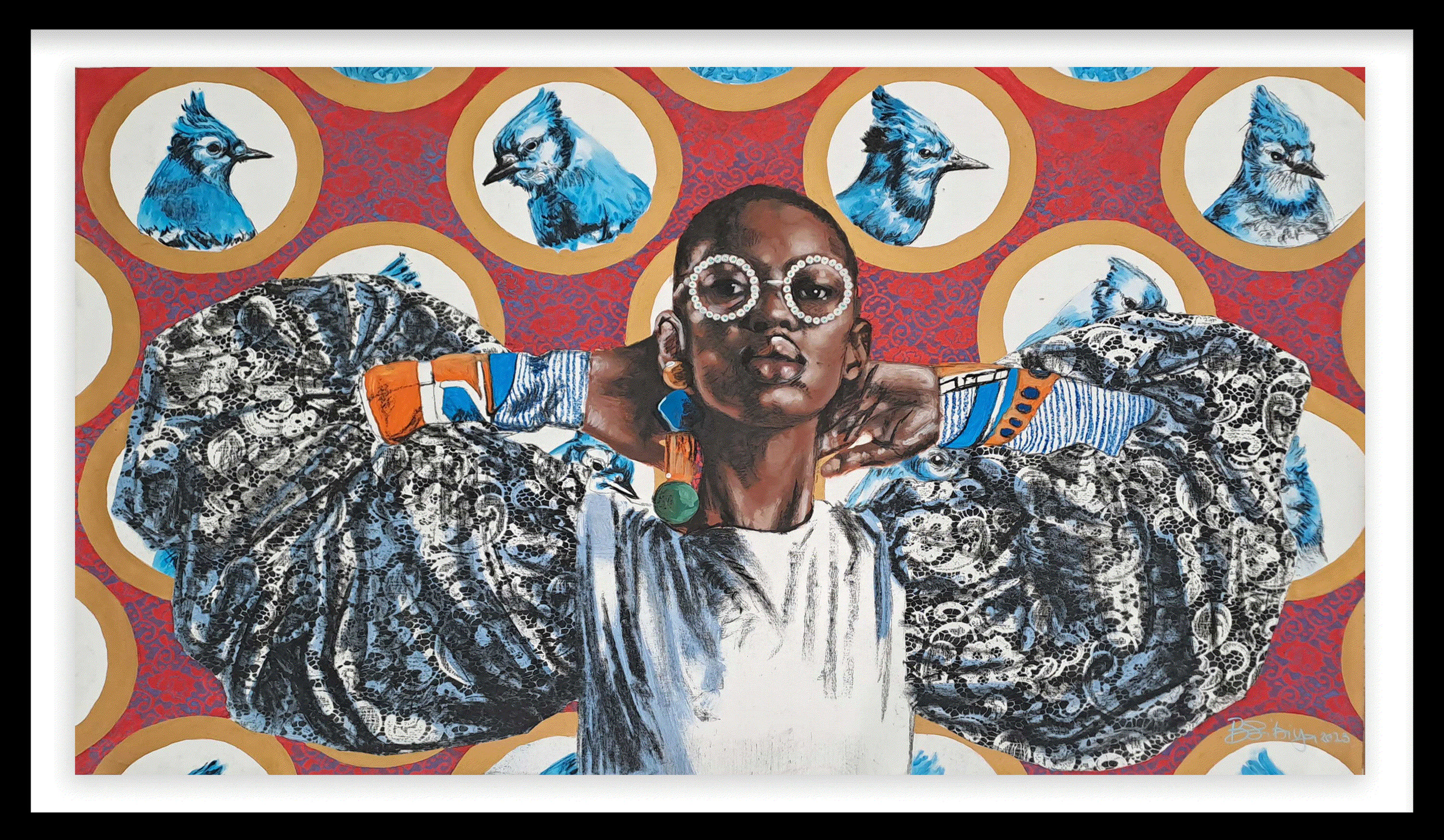

Q: How would you say Swenka culture relates to masculine identity and being part of the working class, within Black communities?A: Swenka Culture is actually not only associated with masculine identity. I had a conversation with a viewer in a gallery about my work and this person told me that the Swenkas I am painting have a feminine touch, because of how they are represented, how I dress them up and the choice of colour I use. If you think about Swenkas, they are mostly associated with Zulu culture, because of the music they embrace, such as LadySmith Black Mambazo. The idea of cleaning yourself up and representing yourself in a beautiful state, most of that is associated with women, because women spend more time in front of the mirror in comparison to men. Today men are becoming more comfortable wearing flamboyant colours, but Swenkas have been doing this. It is rare that within competitions of Swenkas that you find dark and heavy colours, they wear bright colours because they want to be seen. The idea of beauty itself is mostly associated with women, so I do not see Swenkas as masculine, rather they relate to both genders.

-